By Maureen Jouglain

A study published in July 2017 in the journal Endangered Species Research presents the first records of the migratory movements and winter destinations of blue whales and explores opportunities for designating their critical habitats. The study was conducted by Véronique Lesage, species-at-risk researcher at the Maurice Lamontagne Institute of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (together with her team) and by Richard Sears of the Mingan Island Cetacean Study. They have been tracking North Atlantic blue whales in hopes of learning more about their range and their migratory behaviour. In order to protect the blue whale, which has been designated an endangered species since 2002 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), knowledge of critical areas must be refined in order to establish a protection plan for the species.

Research challenges

Although they are one of the largest animals ever to roam the Earth, little is known about blue whales. Indeed, studying an animal that spends less than 5% of its time at the surface comes with its share of difficulties. Biologists can spend days on the water without seeing a blue whale and encounters sometimes only last a few minutes. It is in this context that research teams ply the waters of the St. Lawrence every summer in search of blue whales. In a recently published study in the journal Endangered Species Research, a total of 24 individuals were tracked between 2010 and 2014 using a satellite tag attached to the animals’ dorsal fin. If successfully placing the transmitter is laborious in itself, making sure it stays there is by far the greatest challenge, as the majority of tags fall off after a few weeks. The quest for results requires a great deal of patience for researchers.

After seven years of monitoring, results beginning to emerge

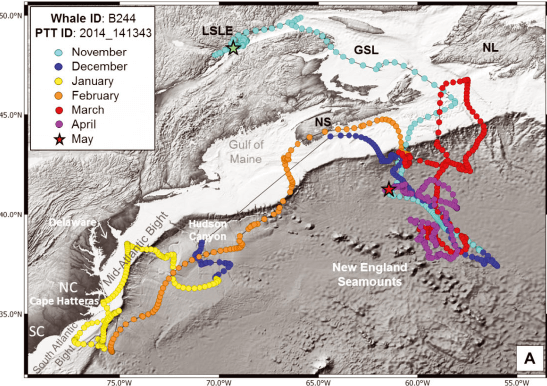

In the study, tags deployed on two females in two different years recorded migratory movements and winter destinations. The first, Symphonie (B244), was an unparallelled informant for researchers, as they were able to track her movements for several months. The transmitter indicates that she travelled 11,918 km in seven months, a distance that is hard to imagine from our perspective. Her journey took her down the St. Lawrence Estuary, then southward along the US coast to South Carolina. She also spent a good bit of time along a submarine mountain chain in the Atlantic. This sector is 5 km deep and is of great interest to biologists, as many species seem to frequent it. Several studies show humpback whales, sperm whales and even puffinspassing through this area: “it might represent a global point of interest,” comments Richard Sears. However, practically nothing is known about these regions. These data are making researchers rethink the classic view of the migratory cycle of baleen whales whereby these migratory species alternate between periods of feeding and long fasts as they travel from their feeding grounds to their breeding grounds. In fact, they are very likely to encounter highly productive areas along the way such as the Atlantic seamounts, and to stop there to feed in winter and spring:

The movements of the second female, Pleiades (B197), who was tracked for nearly three months, echo those of Symphony. This is good news for these researchers, who hope to ascertain more general migration patterns based on these results. Moreover, the fact that they are two mature females is all the more interesting because they probably visited their breeding grounds during the tracking period. In an interview with Radio-Canada, Véronique Lesage explains that for a population such as North Atlantic blue whales with reproductive issues, this information is valuable and more in-depth research can help understand whether there are problems specific to these areas.

As for the other tagged individuals, they nevertheless provide us with information about autumn habitat use in the Estuary and the Gulf. By combining the results of the observational studies with the clues provided by the tags, new feeding grounds can be distinguished: the waters off the Gaspé Peninsula and Chaleur Bay, as well as a number of sectors at the edge of the continental shelf off Nova Scotia. These data correspond to areas containing high concentrations of krill. These results are significant because the blue whale is known to feed almost exclusively on these small crustaceans.

Efforts must continue

Although the population sample is small, the information obtained helps guide future research to the identified areas and thus better understand their role and importance in the annual cycle of blue whales. In particular, they provide for a much broader view of the extent of their range. For Richard Sears, it is a daunting task for humans to fathom the use of such a vast territory: “their time in the waters of the St. Lawrence represents a very small chapter in their lives, and it is quite possible that their habitat encompasses the entire North Atlantic.” These elements make developing a protection plan all the more difficult. Efforts must therefore be continued and international involvement will be needed to better characterize the areas of recurrent use by these blue giants.