Gaspar

Humpback Whale

-

ID number

H626

-

Sex

Female

-

Year of birth

2005

-

Known Since

2006

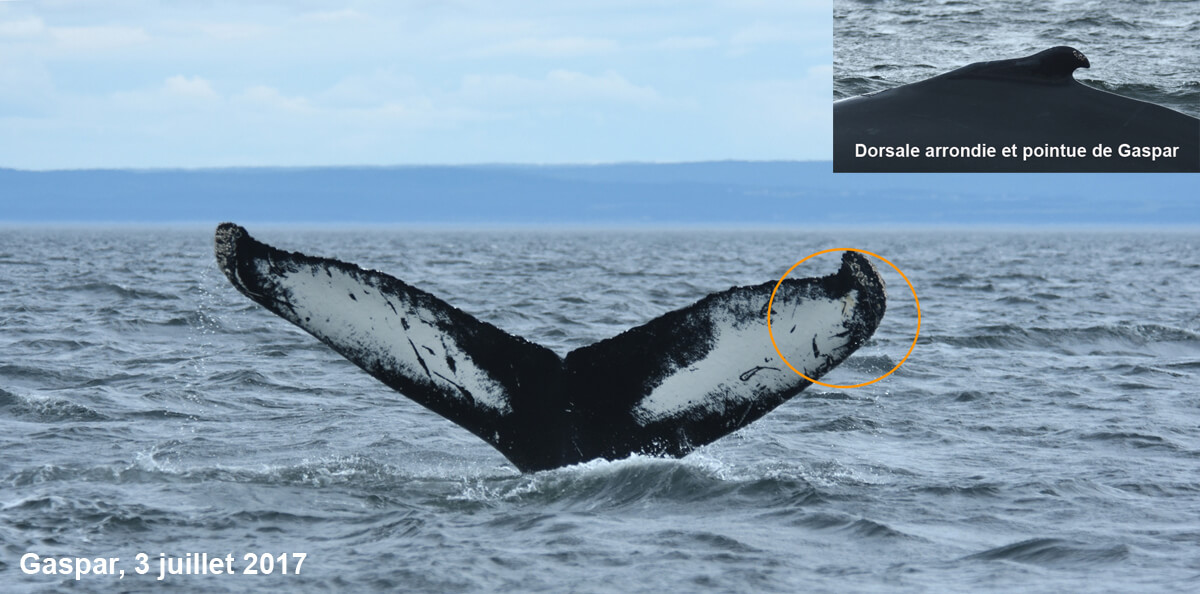

Its distinctive traits

Gaspar is recognizable by the coloring pattern behind her tail. On the right lobe, we can see the profile of the famous ghost that gave it its name.

It has a very curved and pointed dorsal fin.

Its story

This female humpback whale is known as “Boom Boom River (BBR)” in the Gaspé and Mingan Islands. This nickname refers to the municipality of Rivière-au-Tonnerre, locally called “BBR”. It is near this place that the MICS would have made the first observations of the individual in 2005, its year of birth.

Gaspar is the daughter of the female Helmet (H166). Helmet has been followed by the MICS since 1990 and is known as a fan of the Blanc-Sablon and Minganie regions. It was in these areas that Gaspar spent her first summer; however, the following year, the young female opted to visit the Estuary. She thus broke the rule that a young humpback whale must return to feed where her mother brought her. Gaspar has adopted the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park and has been observed there every year since 2006, with the exception of 2008.

In 2017, the MICS team placed a suction cup tag on her while she was in Gaspé. The data taken by the tag should inform researchers about her diving behavior and health status.

Observations history in the Estuary

Years in which the animal was not observed Years in which the animal was observed

Latest news from the publications Portrait de baleines

Depending on the region you are in, this 16-year-old female humpback whale changes her “identity”! In the Mingan and Gaspé areas, she is known as Boom Boom River (BBR), in reference to the municipality of Rivière-au-Tonnerre where the Mingan Island Cetacean Research Station (MICS) team first observed her in 2005. At that time, she was the newborn of the year and accompanied her mother Helmet, a regular visitor to Blanc-Sablon and the Mingan Archipelago. The following year, we expected her to return to this region, as young humpback whales tend to feed in the areas previously visited with their mother. But she surprised us by visiting the St. Lawrence Estuary alone, where she has been seen almost every year since. It was there that she acquired the name Gaspar – a reference to the ghostly silhouette on her tail – following a contest organized by GREMM.

Has Gaspar become an exclusive devotee of this region? Not necessarily. Since 2008, René Roy, MICS collaborator, has been crossing her every year in the Gaspesian waters at the beginning of the season. Thanks to its movements in the Gulf and in the estuary, Gaspar is studied by both MICS and GREMM. Thus, in 2013, 2015 and 2017, she was fitted with a tag to better document her diving behavior and health status.

Some humpback whales can be seen in several sectors of the St. Lawrence during the same season. Their mobility generally varies according to the abundance, density and accessibility of their prey. The number of humpback whales in the St. Lawrence has been increasing since the late 1990s. While only the Siam humpback whale was observed in the Estuary, more and more of them are staying there, as Gaspar does. The expansion of North Atlantic humpback whale ranges is partly explained by their recovery: as their population size increases, they tend to explore new feeding grounds.

In 2019 and again in 2021, Gaspar is observed with a calf. Will her calves adopt their mother’s feeding grounds, or will they inherit her non-conformist character and seek new summer territories?

Gaspar was seen with her first calf in the Gaspé Peninsula in early July, then in the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park. Female humpback whales reach sexual maturity around their sixth year of life. So why hadn’t a calf ever been documented for Gaspar, who is nearly 15 years old? It’s hard to say. Bringing a pregnancy to term requires sufficient food to meet the mother’s energy needs and those of the baby. Stressful situations, such as entanglement, interfere with the ability to reproduce. Perhaps Gaspar simply hadn’t found a male. But now that we know Gaspar is fertile, maybe we’ll see her with a new calf in two or three years.

Gaspar is back in the Marine Park! This humpback whale has been known since 2006 and is recognizable by its under-tail pattern. On her right lobe, one can make out the shape of a ghost, which is where she gets her name. Another distinctive feature is her dorsal fin, which shows a pronounced curve and a pointy tip. In the Gaspé and Mingan Archipelago regions, she is nicknamed BBR, or “Boom Boom River”, the local name of the municipality of Rivière-au-Tonnerre, where she spent her first summer. A the time, the team from the Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS) identified her together with her mother Helmet (H166). Since 2006, Gaspar has visited the St. Lawrence Estuary every year. She is now 13 years old.

Humpbacks and fin whales seem to be particularly abundant this summer! As for blue whales, captains and observers at sea have been reporting that they have not been staying long in the Marine Park. This week, however, several big blues were observed, including at least one with a calf, the famous Jaw-Breaker. Of course, every season is different! During the feeding period, the presence or absence of whales is influenced by the distribution of food and prey. During the months of June and July, numerous observations of capelin were reported in the St. Lawrence Estuary. Like herring, capelin is a forage species, which means it is not at the top of the food chain. It therefore serves as food for other species. These species feed on krill, one of the blue whale’s favourite foods. This species seeks immense plumesof these small planktonic crustaceans to feed on. Could the strong presence of capelin schools this season have contributed to smaller concentrations of krill in mid-summer? Might they have been responsible for the unusually brief incursions of blue whales in the region? For sure, these schools of capelin were appreciated by humpbacks, which prefer fish over plankton.

By Audrey Tawel-Thibert

Seen at the beginning of June in Gaspésie, where she was fitted with a suction cup tag to better understand her diving behavior and health, Gaspar (H626) is now in the Estuary! It is the smiling ghostly face in the grooves of his upper right tail lobe that gives Gaspar his name. Its dorsal fin also contributes to identifying it easily: it is very curved and ends at a sharp point.

This female humpback whale is nicknamed Boom Boom River (BBR) in the Gaspé Peninsula and the Mingan Islands. It was so named in the Gulf in reference to the municipality of Rivière-au-Tonnerre, locally called BBR, near which the first observations of H626 were reported by the Mingan Islands Cetacean Research Station (MICS) in 2005.

Megaptera are well appreciated by the public; their popularity is mainly due to the spectacular behaviours that can be observed in this species. Tails gracefully presented at the time of the dive, strikes on the surface of the water with pectoral fins a few meters long, repetitive tail slapping, head out of the water (“spyhops”), acrobatic jumps; these are impressive maneuvers that delight observers.

Feeding techniques are also striking: it is the case of the nets of bubbles that can be noticed on the surface, produced thanks to the blowhole or the mouth of the cetaceans (this is still a debated question) and which constitute a curtain of bubbles with a conical appearance aiming at gathering and imprisoning the preys. Gaspar has been caught using this method recently, and the cruisers were even able to spot bubbles on the surface of the water!

An interesting specificity, unique to the humpback whales of Southeast Alaska, involves several individuals attacking a school of prey; a single whale produces a circle of bubbles to hold the fish (often herring) while another one emits powerful vocalizations intended to frighten away the booty that will then close in. Mouths wide open, the whales then push the food to the surface and engulf their feast while rolling.

Gaspar, known as Boom Boom River (BBR) in the Gaspé, is recognizable by the colour pattern on the underside of her tail. Her right lobe shows the shape of the famous ghost to which she owes her name. Also, her dorsal fin is curved and pointed in shape. Gaspar was observed in the Marine Park on July 29, 2016. Born in 2005, she followed her mother Helmet, a regular visitor to the waters off the coast of Blanc Sablon and the Mingan region. She first visited the Estuary alone the year after she was born. She has been observed there annually ever since. Gaspar is one of the young humpback explorers who have adopted the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park. She has been photo-identified by the Mingan Islands Cetaceans Society (MICS) and is part of their humpback whales identification catalogue.

Gaspar is a humpback whale, which is one of the species targeted by visitors. To spot humpbacks, one must watch offshore from land-based sites or aboard cruise ships, with the naked eye or with binoculars. Whenever large, powerful blasts are being blown into the air, it is a sign that large whales are in the area. This is also a good sign to identify them! Fin whale? Blue whale? Or humpback? A large column-shaped spout visible several kilometres away is that of either a blue whale (over 6 metres high) or fin whale (4 to 6 metres high). That of the humpback whale is wider and cauliflower-shaped. As for minke whales and belugas, their spouts are smaller, which makes them difficult to see, but not impossible! However, the weather conditions can easily fool us!

Gaspar, known as Boom Boom River in the Gaspé, where she spent a considerable part of the summer, was seen in the Marine Park (Fosse à François sector) by the GREMM – Fisheries and Oceans Canada team on Wednesday, August 5 around 6 am. Since then, she has been seen every day, sometimes in the company of fellow humpback Aramis.

Born in the warm Caribbean waters in the winter of 2004-2005, this female humpback followed her mother Helmet for her first spring migration to the St. Lawrence. Helmet has been been faithful to the Blanc-Sablon and Mingan regions since 1990 (according to observations by the Mingan Island Cetacean Study, (MICS). The following year, 2006, Gaspar was already back exploring the Estuary without her mother. That summer, Gaspar was often seen swimming in tandem with Pi-rat, a young male born the same year as her. These associations between humpbacks are generally unstable and short-lasting. The following year, Pi-rat and Gaspar were still seen together, though much less often. Since this initial observation in 2006, Gaspar has visited the Estuary every year. She owes her name to the ghost-shaped marking on the upper side of her right fluke, in the white part. Another way to recognize her is by her highly curved and pointy dorsal fin.

On August 5 at 6:25 am, a VHF tag was installed on Gaspar’s back. In the course of this tracking, the tag recorded a feeding period in deep waters (up to 120 m), followed by a period of shallower dives with no signs of feeding. We recognize these periods as a function of the “shape” of the dives recorded by the tag. A V-shaped dive is a sign of an exploratory dive while a U-shaped dive characterizes a feeding period. A prolonged period at the surface reveals either a period of rest or travel.

Si Gaspar passe du temps dans l’estuaire chaque été, elle se déplace aussi dans le Saint-Laurent. Le 17 mai, elle a été vue en Gaspésie par le MICS et par un membre du GREMM; le 3 juillet, première observation dans l’estuaire par le GREMM avec Tic Tac Toe et Irisept; mi-juillet, à Gaspé; depuis le 30 juillet, à nouveau dans l’estuaire.

Gaspar a neuf ans cette année. Ayant atteint sa maturité sexuelle à cinq ans, elle serait en âge de procréer. Peut-être la verra-t-on au cours des prochaines années avec un jeune à ses côtés? Les femelles rorquals à bosse donnent naissance à un seul baleineau, dans des intervalles variant d’un à cinq ans. La gestation dure 11 à 12 mois et l’allaitement 5 à 10. Les petits restent un an, voire deux avec leur mère.

Si nous pouvons raconter l’histoire de Gaspar, si nous connaissons son sexe et savons qui est sa mère, c’est grâce à la technique de biopsie (biopsie de Gaspar effectuée par le MICS en 2005). On prélève cet échantillon de peau avec une arbalète projetant une flèche sur le dos de l’animal. Le dard de la flèche se remplit de quelques grammes à peine de peau et de gras. Avec les cellules de la peau, un laboratoire effectue l’analyse de l’ADN de l’individu. Aux chercheurs ensuite de comparer les séquences génétiques de deux ou plusieurs individus pour établir leur éventuel lien de parenté. Dans le cas de Gaspar et de sa mère Helmet, les deux femelles ont subi une biopsie. Le fait de les voir ensemble à plusieurs reprises en 2005 a fourni le premier indicateur de leur filiation.

Gaspar fait partie de cette poignée de jeunes rorquals à bosse qui ont adopté le parc marin du Saguenay–Saint-Laurent. Son premier séjour dans la région remonte à 2006, où elle (et oui, il s’agit d’une femelle…) était venue en compagnie d’un autre rorqual à bosse âgé d’un an, Pi-rat. Ces deux jeunots étaient devenus la coqueluche de l’industrie d’observation, et un concours avait été organisé par le GREMM, conjointement avec le MICS, pour leur trouver des noms appropriés.

L’expertise du MICS avait permis de cibler, dans le patron de coloration sous la queue, les marques qui avaient le plus de chances d’être permanentes, car, chez cette espèce, le patron de coloration se modifie au cours des premières années de vie. À partir de ces marques, les suggestions ont fusé, une liste de finalistes a été constituée, et les gens de l’industrie d’observation sont passés au vote. Gaspar doit son nom au célèbre gentil fantôme, qu’on aperçoit au bout du lobe droit.

Cette année, elle est arrivée dans le parc marin le 25 juin, et a souvent été vue en compagnie de Tic Tac Toe. Des collaborateurs du MICS l’ont photographiée en Gaspésie à la mi-juillet, où elle est surnommée « Boom Boom River ». Le 4 août elle était photographiée par le GREMM à son retour dans le parc marin. Toute une voyageuse!

Dernière heure : Gaspar a été équipée d’une balise le 7 août vers midi, dans le cadre du projet GREMM/Pêches et Océans Canada visant le suivi télémétrique des rorquals du parc marin.

La voici en photos :

Troisième jeune rorqual à bosse à faire son apparition dans le parc marin cet été, Gaspar avait été signalée en Gaspésie au mois de juillet. Elle n’a pas peur d’avaler les kilomètres pour visiter ses secteurs d’alimentation préférés! Sa mère, Helmet, connue du MICS depuis 1990, est plutôt une adepte des régions de Blanc-Sablon et Mingan. C’est là qu’en 2005 elle a amené Gaspar, lors de son premier été. Mais Gaspar, exploratrice, brise la règle qui veut qu’un jeune rorqual à bosse retourne se nourrir sur les lieux où sa mère l’a amené. C’est une fidèle de l’estuaire du Saint-Laurent, qu’elle visite tous les ans depuis 2006.

Les rorquals à bosse sont très appréciés des naturalistes et des capitaines de la région : acrobate et exubérante, cette espèce saute parfois hors de l’eau ou tape la surface avec sa queue ou ses longues nageoires pectorales. Ces nageoires sont d’ailleurs uniques dans le monde animal : elles mesurent le tiers de la longueur totale de la baleine et leur bord d’attaque est dentelé et couvert de petits tubercules. Cette caractéristique a fait l’objet d’une étude publiée récemment : les chercheurs américains ont déterminé que ce relief améliorait la manœuvrabilité et les performances du rorqual à bosse, et ils proposent même d’appliquer cette découverte aux ailes d´avion et aux pales d’éoliennes! À quand un Boeing aux ailes de rorqual à bosse?

Son nom est le résultat d’un concours organisé lors de son premier séjour dans le parc marin. Les gens de l’industrie d’observation de la région avaient retenu ce vocable en l’honneur du célèbre gentil fantôme, qu’on aperçoit au bout du lobe droit.