Gaspar / BBR

Humpback Whale

-

ID number

H626

-

Sex

Female

-

Year of birth

2005

-

Known Since

2006

Distinctive traits

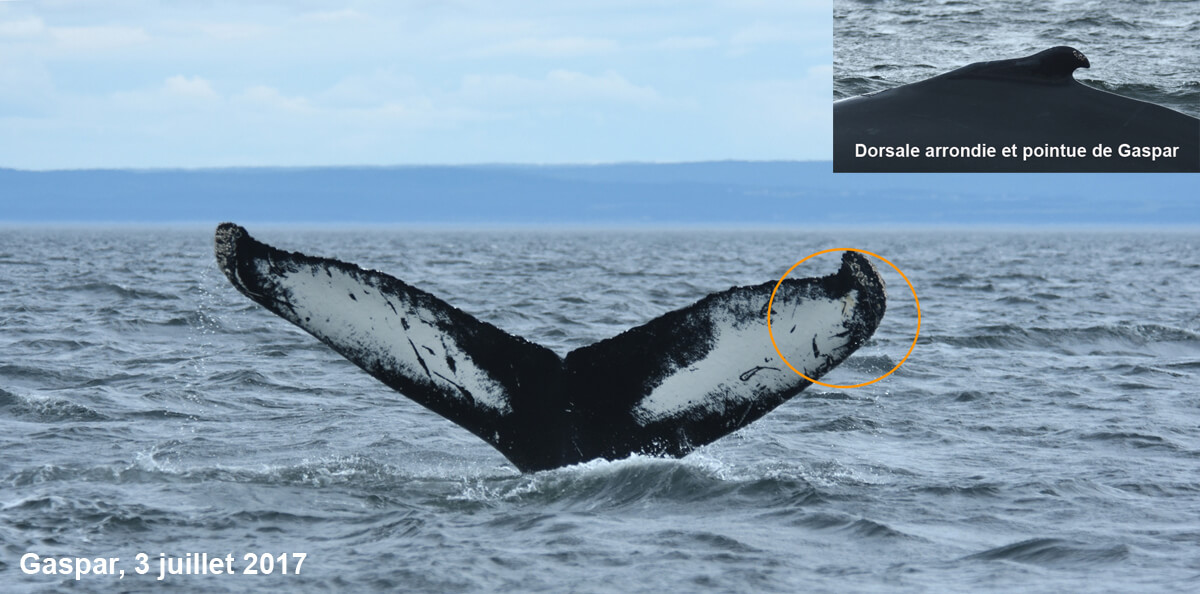

Gaspar is recognizable by the coloring pattern behind her tail. On the right lobe, we can see the profile of the famous ghost that gave it her name.

She has a very curved and pointed dorsal fin.

Life history

This female humpback whale is known as “Boom Boom River (BBR)” in the Gaspé and Mingan Islands. This nickname refers to the municipality of Rivière-au-Tonnerre, locally called “BBR”. It is near this place that the MICS would have made the first observations of the individual in 2005, her year of birth.

Gaspar is the daughter of the female Helmet (H166). Helmet has been followed by the MICS since 1990 and is known as a fan of the Blanc-Sablon and Minganie regions. It was in these areas that Gaspar spent her first summer; however, the following year, the young female opted to visit the Estuary. She thus broke the rule that a young humpback whale must return to feed where her mother brought her. Gaspar has adopted the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park and has been observed there every year since 2006, with the exception of 2008.

In 2017, the MICS team placed a suction cup tag on her while she was in Gaspé. The data taken by the tag should inform researchers about her diving behavior and health status.

Observations history in the Estuary

Years in which the animal was not observed Years in which the animal was observed

Latest news from the publications Portrait de baleines

Gaspar, also known as BBR, is back in the St. Lawrence! First spotted in the Gaspé Peninsula in mid-June by a collaborator from the Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS), this female humpback whale delighted members of the whale watching industry when she arrived in the estuary on the same date as last year: June 27! When she was spotted in the Gaspé Peninsula, Gaspar was not alone. She was swimming alongside another adult individual, who was accompanied by a calf. They could be a mother and her calf, but their identities and affiliation have yet to be confirmed. Humpback whales sometimes associate with each other in the summer at feeding sites, but pairs can sometimes last longer. Affiliations occasionally form between a male and a female—rarely lasting more than two weeks—as well as between two non-lactating females for a few summers. During her very first summer in the estuary in 2006, Gaspar arrived with the young male Pi-Rat (H642), and the two spent six weeks together! Daughter of the humpback whale Helmet (H166), a regular visitor to the Gulf, Gaspar has come to the St. Lawrence Estuary every year since 2006, except in 2008.

Depending on the region you are in, this 16-year-old female humpback whale changes her “identity”! In the Mingan and Gaspé areas, she is known as Boom Boom River (BBR), in reference to the municipality of Rivière-au-Tonnerre where the Mingan Island Cetacean Research Station (MICS) team first observed her in 2005. At that time, she was the newborn of the year and accompanied her mother Helmet, a regular visitor to Blanc-Sablon and the Mingan Archipelago. The following year, we expected her to return to this region, as young humpback whales tend to feed in the areas previously visited with their mother. But she surprised us by visiting the St. Lawrence Estuary alone, where she has been seen almost every year since. It was there that she acquired the name Gaspar – a reference to the ghostly silhouette on her tail – following a contest organized by GREMM.

Has Gaspar become an exclusive devotee of this region? Not necessarily. Since 2008, René Roy, MICS collaborator, has been crossing her every year in the Gaspesian waters at the beginning of the season. Thanks to its movements in the Gulf and in the estuary, Gaspar is studied by both MICS and GREMM. Thus, in 2013, 2015 and 2017, she was fitted with a tag to better document her diving behavior and health status.

Some humpback whales can be seen in several sectors of the St. Lawrence during the same season. Their mobility generally varies according to the abundance, density and accessibility of their prey. The number of humpback whales in the St. Lawrence has been increasing since the late 1990s. While only the Siam humpback whale was observed in the Estuary, more and more of them are staying there, as Gaspar does. The expansion of North Atlantic humpback whale ranges is partly explained by their recovery: as their population size increases, they tend to explore new feeding grounds.

In 2019 and again in 2021, Gaspar is observed with a calf. Will her calves adopt their mother’s feeding grounds, or will they inherit her non-conformist character and seek new summer territories?

Gaspar was seen with her first calf in the Gaspé Peninsula in early July, then in the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park. Female humpback whales reach sexual maturity around their sixth year of life. So why hadn’t a calf ever been documented for Gaspar, who is nearly 15 years old? It’s hard to say. Bringing a pregnancy to term requires sufficient food to meet the mother’s energy needs and those of the baby. Stressful situations, such as entanglement, interfere with the ability to reproduce. Perhaps Gaspar simply hadn’t found a male. But now that we know Gaspar is fertile, maybe we’ll see her with a new calf in two or three years.

Gaspar is back in the Marine Park! This humpback whale has been known since 2006 and is recognizable by its under-tail pattern. On her right lobe, one can make out the shape of a ghost, which is where she gets her name. Another distinctive feature is her dorsal fin, which shows a pronounced curve and a pointy tip. In the Gaspé and Mingan Archipelago regions, she is nicknamed BBR, or “Boom Boom River”, the local name of the municipality of Rivière-au-Tonnerre, where she spent her first summer. A the time, the team from the Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS) identified her together with her mother Helmet (H166). Since 2006, Gaspar has visited the St. Lawrence Estuary every year. She is now 13 years old.

Humpbacks and fin whales seem to be particularly abundant this summer! As for blue whales, captains and observers at sea have been reporting that they have not been staying long in the Marine Park. This week, however, several big blues were observed, including at least one with a calf, the famous Jaw-Breaker. Of course, every season is different! During the feeding period, the presence or absence of whales is influenced by the distribution of food and prey. During the months of June and July, numerous observations of capelin were reported in the St. Lawrence Estuary. Like herring, capelin is a forage species, which means it is not at the top of the food chain. It therefore serves as food for other species. These species feed on krill, one of the blue whale’s favourite foods. This species seeks immense plumesof these small planktonic crustaceans to feed on. Could the strong presence of capelin schools this season have contributed to smaller concentrations of krill in mid-summer? Might they have been responsible for the unusually brief incursions of blue whales in the region? For sure, these schools of capelin were appreciated by humpbacks, which prefer fish over plankton.

Seen at the beginning of June in Gaspésie, where she was fitted with a suction cup tag to better understand her diving behavior and health, Gaspar (H626) is now in the Estuary! It is the smiling ghostly face in the grooves of his upper right tail lobe that gives Gaspar his name. Its dorsal fin also contributes to identifying it easily: it is very curved and ends at a sharp point.

This female humpback whale is nicknamed Boom Boom River (BBR) in the Gaspé Peninsula and the Mingan Islands. It was so named in the Gulf in reference to the municipality of Rivière-au-Tonnerre, locally called BBR, near which the first observations of H626 were reported by the Mingan Islands Cetacean Research Station (MICS) in 2005.

Megaptera are well appreciated by the public; their popularity is mainly due to the spectacular behaviours that can be observed in this species. Tails gracefully presented at the time of the dive, strikes on the surface of the water with pectoral fins a few meters long, repetitive tail slapping, head out of the water (“spyhops”), acrobatic jumps; these are impressive maneuvers that delight observers.

Feeding techniques are also striking: it is the case of the nets of bubbles that can be noticed on the surface, produced thanks to the blowhole or the mouth of the cetaceans (this is still a debated question) and which constitute a curtain of bubbles with a conical appearance aiming at gathering and imprisoning the preys. Gaspar has been caught using this method recently, and the cruisers were even able to spot bubbles on the surface of the water!

An interesting specificity, unique to the humpback whales of Southeast Alaska, involves several individuals attacking a school of prey; a single whale produces a circle of bubbles to hold the fish (often herring) while another one emits powerful vocalizations intended to frighten away the booty that will then close in. Mouths wide open, the whales then push the food to the surface and engulf their feast while rolling.

Gaspar, known as Boom Boom River (BBR) in the Gaspé, is recognizable by the colour pattern on the underside of her tail. Her right lobe shows the shape of the famous ghost to which she owes her name. Also, her dorsal fin is curved and pointed in shape. Gaspar was observed in the Marine Park on July 29, 2016. Born in 2005, she followed her mother Helmet, a regular visitor to the waters off the coast of Blanc Sablon and the Mingan region. She first visited the Estuary alone the year after she was born. She has been observed there annually ever since. Gaspar is one of the young humpback explorers who have adopted the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park. She has been photo-identified by the Mingan Islands Cetaceans Society (MICS) and is part of their humpback whales identification catalogue.

Gaspar is a humpback whale, which is one of the species targeted by visitors. To spot humpbacks, one must watch offshore from land-based sites or aboard cruise ships, with the naked eye or with binoculars. Whenever large, powerful blasts are being blown into the air, it is a sign that large whales are in the area. This is also a good sign to identify them! Fin whale? Blue whale? Or humpback? A large column-shaped spout visible several kilometres away is that of either a blue whale (over 6 metres high) or fin whale (4 to 6 metres high). That of the humpback whale is wider and cauliflower-shaped. As for minke whales and belugas, their spouts are smaller, which makes them difficult to see, but not impossible! However, the weather conditions can easily fool us!

Gaspar, known as Boom Boom River in the Gaspé, where she spent a considerable part of the summer, was seen in the Marine Park (Fosse à François sector) by the GREMM – Fisheries and Oceans Canada team on Wednesday, August 5 around 6 am. Since then, she has been seen every day, sometimes in the company of fellow humpback Aramis.

Born in the warm Caribbean waters in the winter of 2004-2005, this female humpback followed her mother Helmet for her first spring migration to the St. Lawrence. Helmet has been been faithful to the Blanc-Sablon and Mingan regions since 1990 (according to observations by the Mingan Island Cetacean Study, (MICS). The following year, 2006, Gaspar was already back exploring the Estuary without her mother. That summer, Gaspar was often seen swimming in tandem with Pi-rat, a young male born the same year as her. These associations between humpbacks are generally unstable and short-lasting. The following year, Pi-rat and Gaspar were still seen together, though much less often. Since this initial observation in 2006, Gaspar has visited the Estuary every year. She owes her name to the ghost-shaped marking on the upper side of her right fluke, in the white part. Another way to recognize her is by her highly curved and pointy dorsal fin.

On August 5 at 6:25 am, a VHF tag was installed on Gaspar’s back. In the course of this tracking, the tag recorded a feeding period in deep waters (up to 120 m), followed by a period of shallower dives with no signs of feeding. We recognize these periods as a function of the “shape” of the dives recorded by the tag. A V-shaped dive is a sign of an exploratory dive while a U-shaped dive characterizes a feeding period. A prolonged period at the surface reveals either a period of rest or travel.

While Gaspar spends time in the estuary every summer, she also travels in the St. Lawrence. On May 17, she was seen in Gaspésie by MICS and a GREMM member; on July 3, first sighting in the estuary by GREMM with Tic Tac Toe and Irisept; mid-July, in Gaspé; since July 30, again in the estuary.

Gaspar is nine years old this year. Having reached her sexual maturity at five, she would be of childbearing age. Perhaps we’ll see her in the next few years with a calf by her side? Female humpback whales give birth to a single calf between one and five years apart. Gestation lasts 11 to 12 months and nursing 5 to 10. The calves stay with their mother for a year or two.

If we can tell Gaspar’s story, if we know her sex and who her mother is, it’s thanks to the biopsy technique (Gaspar biopsy carried out by MICS in 2005). This skin sample is taken with a crossbow, projecting an arrow onto the animal’s back. The arrow’s sting fills with just a few grams of skin and fat. Using the skin cells, a laboratory analyzes the individual’s DNA. Researchers then compare the genetic sequences of two or more individuals to establish their possible relationship. In the case of Gaspar and her mother Helmet, both females were biopsied. Seeing them together on several occasions in 2005 provided the first indicator of their parentage.

Gaspar is one of a handful of young humpback whales to have adopted the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park. Her first visit to the region dates back to 2006, when she (and yes, it is a female…) came in the company of another one-year-old humpback whale, Pi-rat. These two youngsters had become the talk of the whale-watching industry, and a competition was organized by GREMM, in conjunction with MICS, to find appropriate names for them.

MICS’ expertise enabled us to target those markings in the coloration pattern under the tail that were most likely to be permanent, as the coloration pattern of this species changes over the first few years of life. Based on these markings, suggestions poured in, a shortlist of finalists was drawn up, and the people in the observation industry took a vote. Gaspar is named after the famous gentle ghost at the end of the right lobe.

This year, she arrived in the marine park on June 25, and was often seen in the company of Tic Tac Toe. MICS collaborators photographed her in Gaspésie in mid-July, where she is nicknamed “Boom Boom River”. On August 4, she was photographed by GREMM on her return to the marine park. What a traveller!

Breaking news: Gaspar was fitted with a beacon around noon on August 7, as part of the GREMM/Fisheries and Oceans Canada project to telemetrically monitor rorqual whales in the Marine Park.

Gaspar, the third young humpback whale to appear in the Marine Park this summer, was first reported in Gaspésie in July. She’s not afraid to cover the miles to visit her favorite feeding grounds! Her mother, Helmet, known to MICS since 1990, is more of a fan of the Blanc-Sablon and Mingan regions. That’s where she brought Gaspar for her first summer in 2005. But Gaspar, an explorer, breaks the rule that a young humpback whale must return to feed where its mother brought it. She is a loyal visitor to the St. Lawrence Estuary, which she has visited every year since 2006.

Humpback whales are very popular with naturalists and captains in the region: acrobatic and exuberant, this species sometimes jumps out of the water or taps the surface with its tail or long pectoral fins. These fins are unique in the animal world: they measure a third of the whale’s total length, and their leading edge is serrated and covered with small tubercles. This characteristic was the subject of a recently published study: American researchers determined that this relief improved the humpback whale’s manoeuvrability and performance, and they are even proposing to apply this discovery to aircraft wings and wind turbine blades! When will we see a Boeing with humpback whale wings?

Her name is the result of a contest organized during her first visit to the marine park. People in the local observation industry had chosen this name in honour of the famous gentle ghost, seen at the end of the right lobe.