What if the future of cetacean protection no longer relied solely on humans, but also on artificial intelligence?

In the span of just a few months, this new technology, commonly referred to as AI, has taken society by storm. It is also found in the environmental sector, where it has been helping us protect whales for several years now.

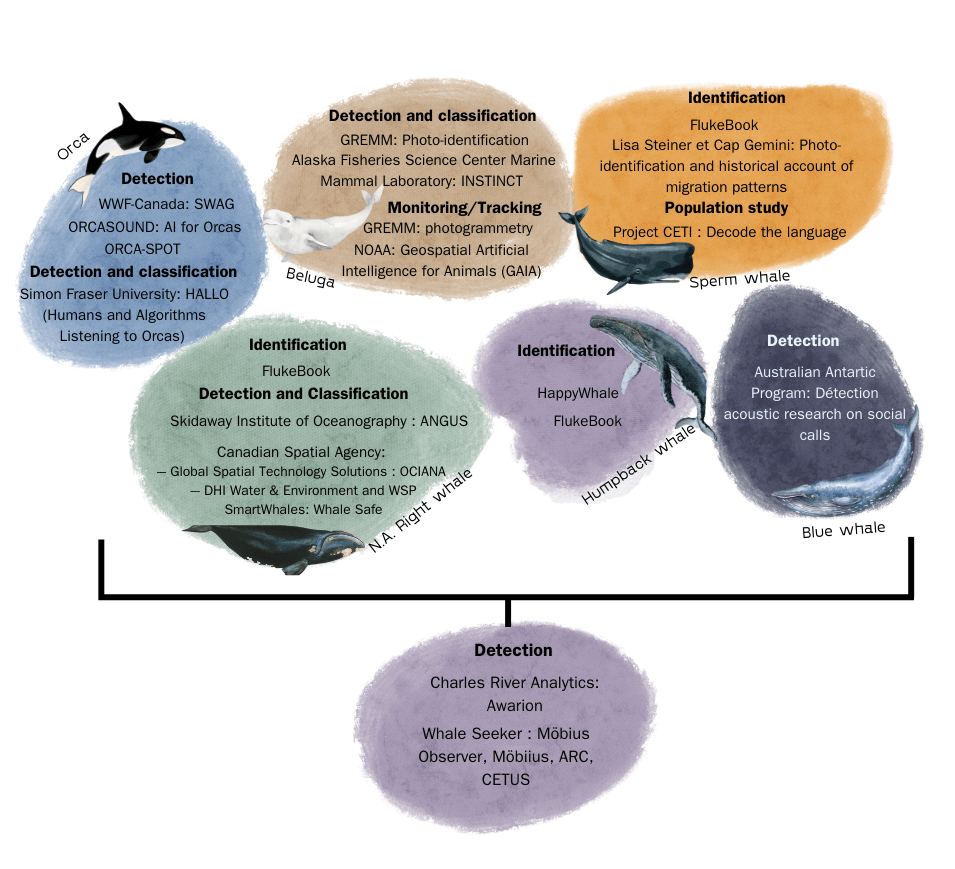

Scientists use artificial intelligence for the detection, monitoring, classification, identification, and long-term tracking of cetacean species, as well as to better understand them. AI covers more ground and provides accurate, up-to-date, and standardized data. Above all, it helps save scientists time! Let’s dive into the somewhat complicated world of this revolutionary tool.

Where are the whales? : Detecting in order to better protect

Detecting a marine mammal with the naked eye requires training and a lot of practice! That’s why many environmental organizations and companies are investing in artificial intelligence to help detect marine mammals. AI systems can detect, analyze and report in real time the presence of ships, fishing equipment and cetaceans several kilometres away. Thus, ships are warned and can slow down and change their course to avoid collisions. Deep-sea mining bases, seismic studies, and wind farm construction can also cease their activities to comply with environmental laws and avoid disturbing or injuring cetaceans.

Made in Quebec!

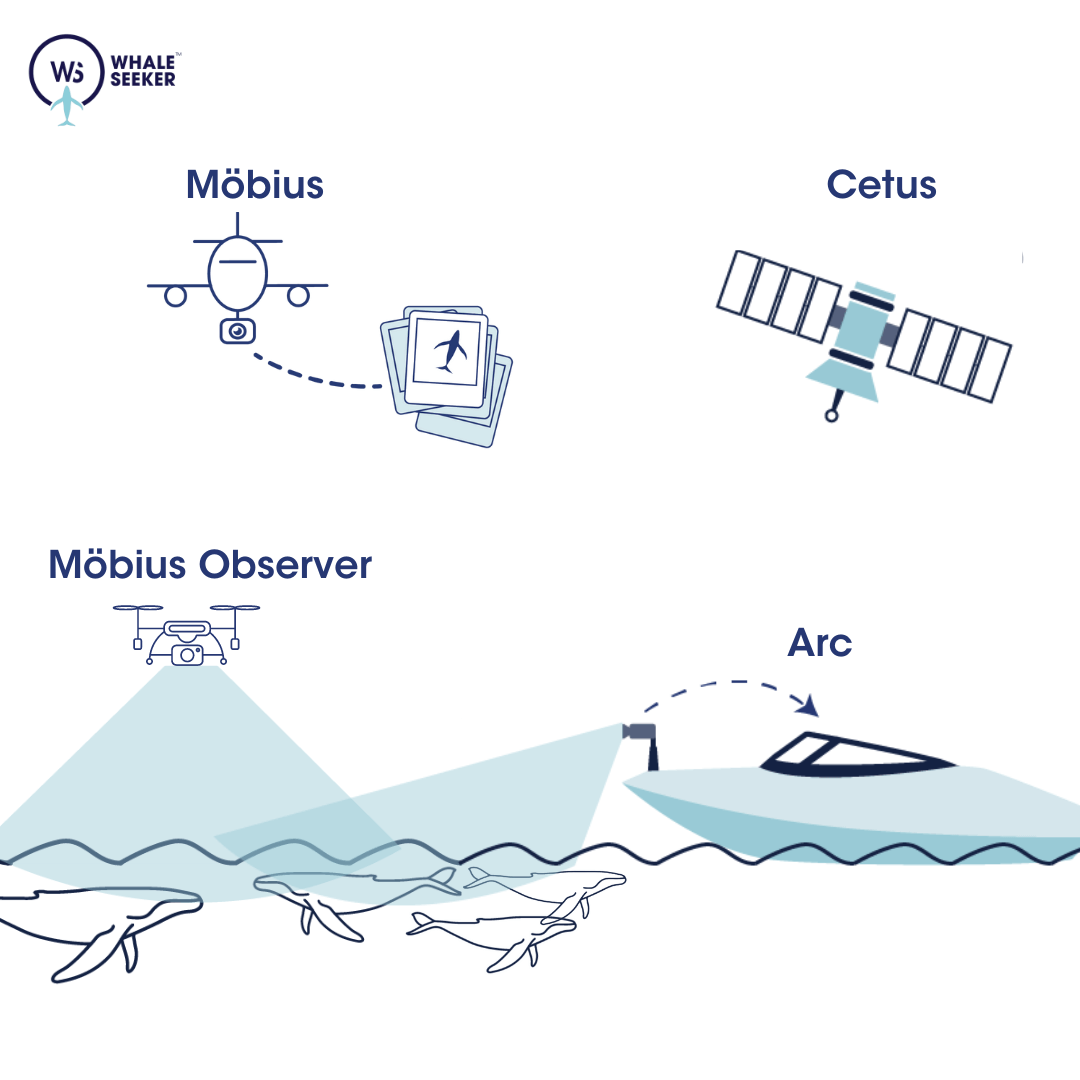

The Canadian company Whale Seeker, in collaboration with the DFO and Edgewise Environmental, has developed new systems for detecting cetaceans using artificial intelligence. One of these AI tools, Möbius Observer, detects whether an animal is present in real time using drones that process images taken in the environment and notify the marine mammal observer (MMO).

Taking the high road

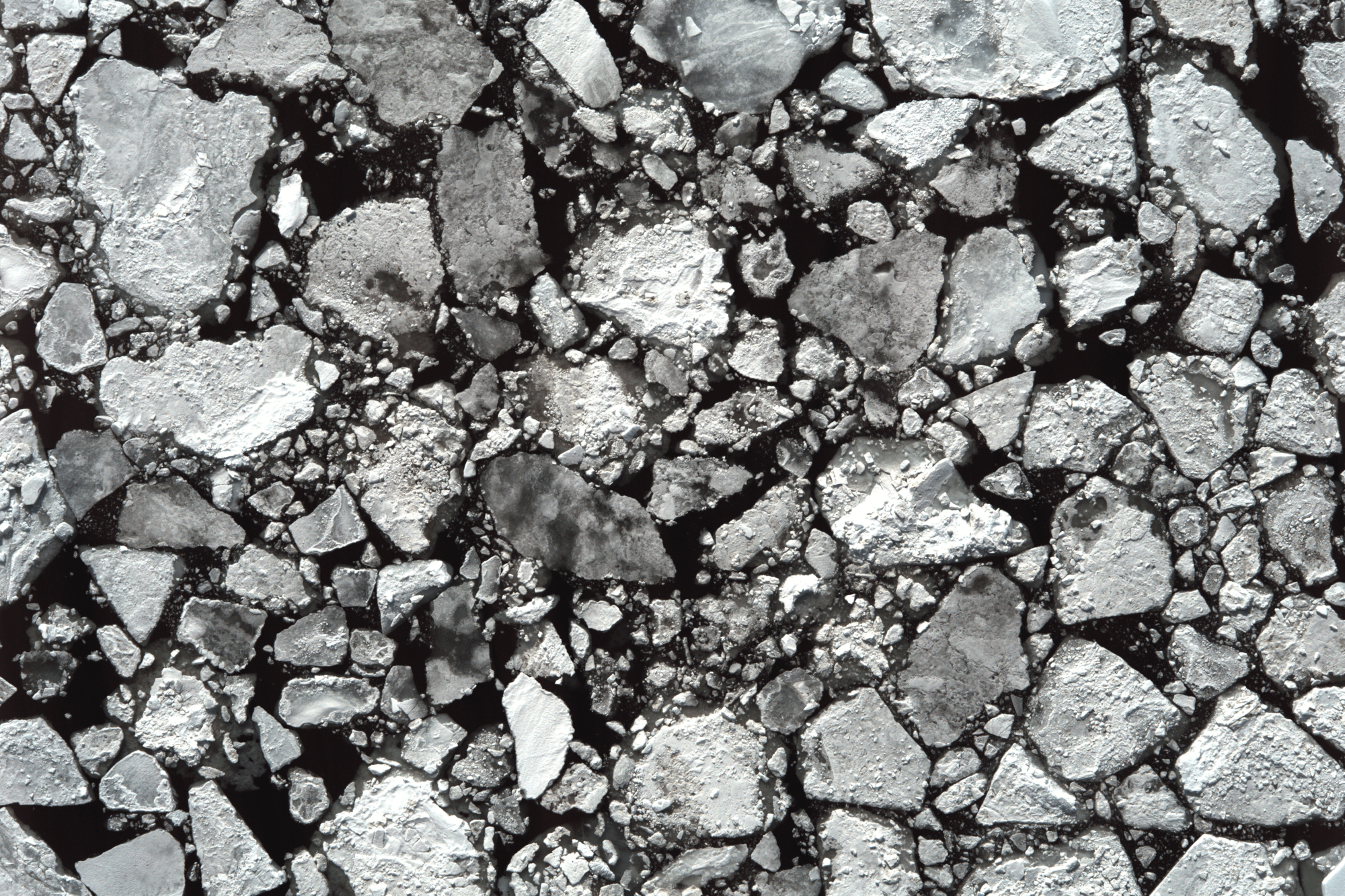

Sometimes, we also have to look for cetaceans from a viewpoint that covers a larger area. These are tasks that require a great deal of rigour and time from analysts!

Global Spatial Technology Solutions (GSTS ) detects North Atlantic right whales from satellites of the Canadian Space Agency. Using modelling data on shipping lanes and the movement patterns of feeding right whales, GSTS hopes to anticipate potential collisions by tracking whales and proximate ships.

To identify high-density areas of endangered populations of North Atlantic right whales and Cook Inlet belugas in Alaska, an initiative of the GAIA (Geospatial Artificial Intelligence for Animals) project detects these cetaceans from high-resolution satellite imagery.

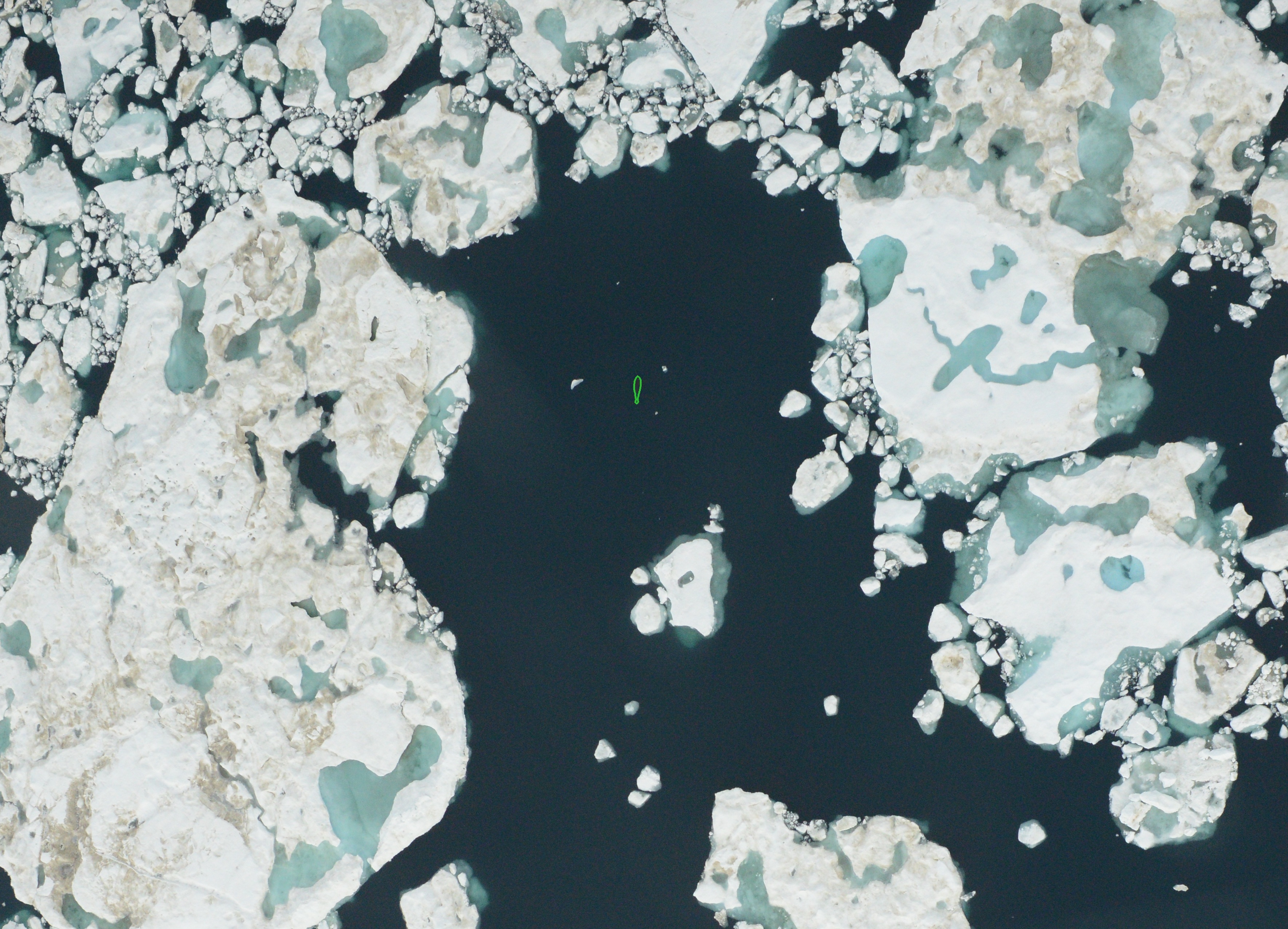

Put yourself in an analyst’s shoes and try to find the marine mammal in this aerial image, which is one of thousands taken in the context of a seal survey.

Listening to cetaceans

Monitoring cetaceans visually from the air or sea can be logistically challenging and costly. For specific analysis purposes, passive acoustics is cost-effective for monitoring mammals over entire seasons and years!

In a species detection and classification project, the Instinct model analyzes months of recordings in search of vocalizations made by Cook Inlet belugas. The model is highly accurate and was able to perform in a single night a job that would take two weeks to do manually. Instinct also detected and classified 18 million fin whale vocalizations in two months, saving scientists 6 years of work. Additionally, it provided answers regarding the seasonal distribution areas of these fin whales in the Bering and Chukchi seas.

In the St. Lawrence, researcher Clément Chion is developing AI together with the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals (GREMM) to detect beluga calls from thousands of hours of acoustic recordings. They hope to be able to locate and make predictions about the future positions of the belugas heard. In this case, AI will help better manage the environment that these white whales share with human activities. AI is being implemented globally and locally!

Monitoring these animals visually from air or sea is difficult and expensive. Passive acoustic monitoring – listening underwater – is a cost-effective method to monitor marine mammals over seasons and years.

Finding the right whales with their vocalisations

In the US, NOAA and the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography are using an underwater robot equipped with a hydrophone called Angus. This intelligent system contains a library of this species’ vocalizations, which allows it to identify the presence of an individual in the ambient hubbub of the ocean. Alerts are sent out to ship captains in real time to warn them to slow down in areas of high maritime traffic, especially near the coasts and major ports.

The waters off the southeast coast are a blind spot in the network of US research centres tracking right whales along the Eastern Seaboard.

In partnership with the Gitga’at First Nation and the North Coast Cetacean Society, WWF-Canada has been spearheading the SWAG project in British Columbia since 2020. Four GPS-equipped hydrophones monitor 200 km2of water in the Squally Channel in an effort to detect the sounds of cetaceans as well as the animals’ locations, numbers and movements. The algorithm differentiates the sounds (some of which are inaudible to the human ear) of killer whales, fin whales and humpback whales. The more data are collected, the better the tool will be able to associate vocalizations with behaviours (socialization, feeding, etc.); this is called machine learning!

AI for identifying and classifying: The challenge of belugas

Many research centres are now incorporating AI to save scientists time on specific tasks that are rather monotonous… like identifying cetaceans! Performing this arduous work manually is highly time-intensive due to several factors that vary depending on the species being studied. Image quality varies, as does the time spent identifying individuals.

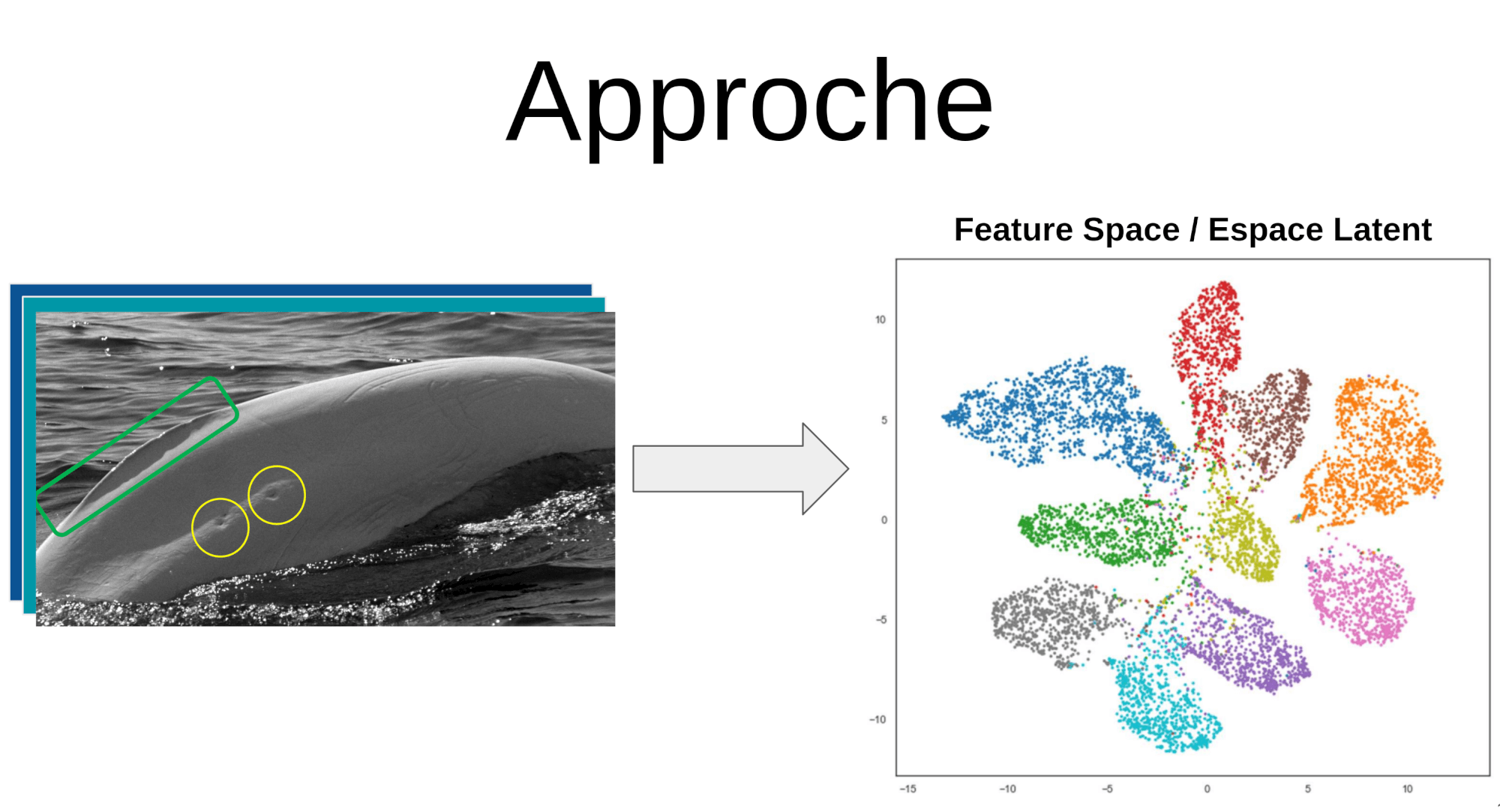

Let’s look at an example right here in Quebec: identifying belugas. Belugas are particularly difficult to identify due to their colour, which changes over time. They even have markings that disappear! The only way to correctly identify them is by using distinguishable markings on their flanks or on their dorsal ridge. In a single day of research on the water, scientists may take hundreds of photos of belugas.

Photo-identification requires a great deal of concentration and is highly repetitive. This is where artificial intelligence comes into play. AI software isolates the belugas, which are often swimming close to one another, and crops them individually into new photos. It also distinguishes the left and right sides, in addition to identifying belugas that are already known by the organization. Otherwise, the animal will obtain a new code unique to that individual.

Photo-identification requires a great deal of concentration and is highly repetitive. This is where artificial intelligence comes into play. AI software isolates the belugas, which are often swimming close to one another, and crops them individually into new photos. It also distinguishes the left and right sides, in addition to identifying belugas that are already known by the organization. Otherwise, the animal will obtain a new code unique to that individual.

Who am I?

AI also helps classify belugas according to location, type, and degree of markings such as serious injuries, scars, spots, etc. This allows scientists to more easily compare and identify a potential match by grouping individuals with similar markings.

AI for population monitoring

AI can be used to assess the health of cetaceans. A GREMM research team also plans to incorporate AI into photogrammetry to monitor the St. Lawrence beluga population. Photogrammetry – an almost complete measurement of the animal – can be used to assess physical condition, identify pregnancies and even differentiate males from females, all in a non-invasive manner. AI will save scientists time by measuring animals automatically and quickly! A similar development technique for monitoring large rorquals could also be developed.

These data are used to monitor the well-being of cetaceans and determine whether or not a population is adapting to changes in its environment.

Future conservation: intelligent but responsible

There is no doubt that AI is important and could become essential in the protection of endangered species. It can contribute to the detection, identification, and understanding of the social structures of cetaceans and how they communicate. It can provide additional insight into the study of populations, whether it be with regard to their size, distribution, or longevity. AI can be used to understand how cetaceans use their habitats and to map migrationpatterns. Tracking and identifying cetaceans by computer is a less invasive method because it does not require tagging.

AI can shorten the time between detection and decision-making, in addition to providing access to recent data. Reliable, quickly transmitted data can be nothing but beneficial for economic, social, political, and environmental decisions that concern wildlife conservation.

Challenges and limits

However, AI also comes with its share of obstacles. First of all, for it to be effective and accurate, it must be fed a large volume of data. Errors are always possible and the data may be inaccurate. Humans must remain invested in AI, as it will always require the expertise of scientists who are familiar with the species. It must also be ensured that the use of this technology remains responsible and scientific, and that it is not misused for other purposes such as poaching, whaling ships or mass tourism.