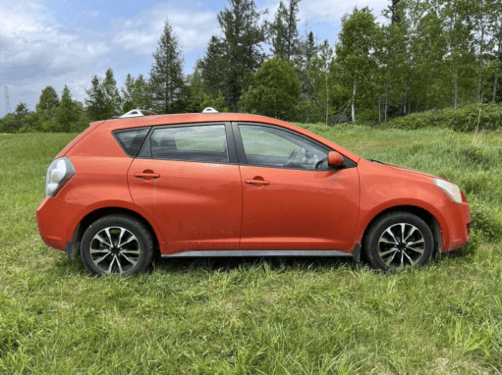

June 11: The day didn’t begin aboard the Antarès or any of GREMM’s other boats, but rather in Michel Martin’s bright orange 2010 Pontiac Vibe. It may not look like much, but this vehicle single-handedly transported the entire brand-new beaked whale that is now on display at CIMM! Where were we headed on this gloomy morning? To our partner, the Cinq Étoiles farm, to help clean whale bones for a future exhibit! In this field report, Lilly and Benjamin, who work in the Whales Online editorial department, will transport you to the slightly disgusting but oh-so-interesting world of preparatory maintenance of GREMM skeletons.

Bones, bones and more bones!

Michel drives us in his car to GREMM’s storage shed. A mandatory stop to pick up the equipment we’ll need for the day ahead: knives, metal brushes, rain boots (not for walking through puddles, but rather to protect us from patches of grease-soaked dirt), etc.

Back on the road, this time headed to the Cinq Étoiles farm. GREMM’s facilities are a bit inland, where there is no electricity or running water. Water is pumped from a nearby pond, and the elements are powered by propane. Several skeletons are stored there: a white-beaked dolphin, a beluga with severe scoliosis, and, lastly, a rare species: a True’s beaked whale. Bones, bones and more bones!

Soon after we arrive, our team members slip into their boots and douse themselves with mosquito repellent. Our day can finally begin. We’re lucky, as the weather is cloudy and not too hot. Our mission that morning is to remove the remaining organic tissue from the bones of the white-beaked dolphin’s pectoral fins. The work is already well underway. Michel puts a couple large pots of water on to boil. This is a repetitive process. The bones must be boiled to soften the remaining flesh while taking care not to alter the bone structure. Then they must be scraped with a knife or a wire brush. These steps must be repeated over and over until the bones are clean. Once this phase is complete, similar tasks must be performed to degrease the skeletons, alternating between soaking and drying.

After hours of scraping, it’s finally time for lunch. We take the opportunity to interview Michel, beginning with the emotions this work triggers in him. “Nostalgia,” he initially answers. He recalls the various experiences he has had, often accompanied by his colleague Patrick. He describes their relationship as if they were “each a hemisphere of the same brain.” Secondly, he mentions the heat, which can be sweltering in the flat terrain around Sacré-Coeur.

We asked if he had any stories to share with us about cleaning whales. Although many people find the stench repulsive, small animals often seem indifferent to it. Small creatures often find their way into the equipment and the bones themselves. Michel tells us that when they were cleaning Piper, CIMM’s right whale, they had to create large pools of water to soak the bones. In one of the basins was the animal’s skull. The water was poured in gradually. As the water level rose, more and more mice scurried out of the skeleton’s orifices. There were more than twenty of them! The only bugs we encountered were the flies and mosquitoes that wanted to eat us alive!

After we finish our break, we get back to work. The day continued like this. A seemingly endless alternation between soaking and scraping. It wasn’t just the pectoral fins that were being stripped of their flesh. Under Michel’s supervision, numerous bone-filled plastic bags were handled.

The day was drawing to a close. The equipment and bones had to be put away and the tools loaded into the car to be taken back to the shed. The team took off their gloves and rain boots and piled into the car. This is how the day ended with a “carrion scraper.”

Homage to behind-the-scenes work

This report is dedicated to all these carrion scrapers that are too often forgotten. Awed by the whale skeletons hanging from the CIMM’s ceiling, visitors often wonder how they were assembled, but they forget about the most time-consuming and perhaps least liked step: cleaning the bones. A putrid funk, thousands of larvae, a blazing sun: It’s an inglorious but necessary task, says Michel Martin, one of GREMM’s experienced naturalists. For several years now, he has been recognized as the resource for preparing skeletons for display at CIMM. He has taken on this challenging and stinky responsibility, often with his sidekick, Patrick Bérubé. Together, they are the brains and muscles behind several CIMM beauties like Piper the North Atlantic right whale, Bergeronnes the fin whale, Godbout the humpback whale and the Sowerby’s beaked whale. They are not alone behind the scenes. Many folks have rolled up their sleeves and gotten their hands dirty throughout the process! Nevertheless, volunteers don’t just appear out of thin air when it comes to playing with the dead. The steps to get there are manifold and tedious.

New skeletons?

The bones at the Cinq Étoiles farm are part of GREMM’s latest skeleton projects. It’s simply a question of space in the exhibition hall, which was most recently expanded in 2020! However, when we asked him whether certain individuals could break this moratorium on future skeletons, he was very clear: “It’ s important that any additional skeleton bring something new to the museum. A killer whale or other exceptional individual that we don’t often see in the St. Lawrence could certainly be interesting.” Stay tuned for these future additions to the exhibition hall!