There are many places around the world that lend themselves to watching whales, but some of them are unique. Last winter, I had the chance to visit one of these places, which is as exceptional as it is remote. These are Japan’s volcanic Ogasawara Islands in the Pacific, far from any land mass and in the heart of the ocean swell.

My mission: to collect sounds and images of the cetaceans that live there, to support both my personal projects and the educational materials used for training courses offered by the Marine Mammal Observation Network. I’m therefore taking advantage of this article to share information about this rather incredible place, as well as some of the sights and sounds I was able to capture there.

Journey to a far-flung archipelago

The trek to the Ogasawara Islands is not exactly straightforward and presents a number of challenges. To reach this isolated yet highly important place for cetaceans, you must first travel to Tokyo, one of the largest cities in the world. Once you get there, you must then figure out how to get around while navigating the culture and especially the signs in the Japanese capital.

Regardless how you get there, the ultimate goal is to arrive on time at Tokyo’s Takeshiba Passenger Ship Terminal, which is located at the mouth of the Sumida River. Here, against a backdrop of skyscrapers, we find the only ferry that makes the weekly journey to the archipelago. For the adventure to begin, all that’s left to do is to show your ticket (reserved and printed in advance) toone of the terminal agents, who will welcome you aboard the Ogasawara-Maru.

Once passengers have settled into their cabins and the departure time arrives, the ferry sets out from the port, embarking on a 1,000-kilometre southbound journey that will last 24 hours. This crossing takes us from the busy industrialized port of Tokyo to the remote and pristine Ogasawara Islands. Along the way, swells and stiff winds translate into bouts of seasickness, while albatrosses, shearwaters, and the occasional back of a whale entertain those brave enough to stand on the deck with their eyes peeled.

Whale-watching paradise

After a full day on the water and a few sporadic cetacean sightings, the ferry finally arrives at the largest island in the archipelago, Chichijima. It is in this small, tropical and sunny town that the adventure of documenting these animals takes on its full meaning. Indeed, the island’s main village is replete with souvenirs, signs and statues depicting these giants of the sea. There’s also an exhibition on cetaceans, not to mention a multitude of companies and individuals offering offshore whale-watching tours. Throughout all these activities, the local Ogasawara Whale Watching Association manages and regulates offshore adventures, in addition to conducting research on these animals. Without a doubt, cetaceans are a major component of the archipelago’s identity.

In addition to being present on land, they also grace the seas. Several species of cetaceans frequent the local waters, the most common of which include humpback whales, sperm whales, spinner dolphins, and bottlenose dolphins. Humpbacks are observed close to the coast between February and April, which is when they mate. These individuals are believed to be part of one of the populations that frequent the North Pacific the remainder of the year. The other three species are present year-round. Bottlenose dolphins can be observed near the islands, while sperm whales tend to be found farther offshore, where water depths exceed 1,000 m.

There are also spinner dolphins, which are believed to make daily transits between the archipelago’s calm bays and the high seas, where waters are rough but rich in prey. A further 20+ species also live around the archipelago or pass through the region on migration. This list includes fin whales, dolphins, and even beaked whales, which are believed to frequent the surrounding deep waters and the Mariana Trench, which lies roughly 100 kilometres from the archipelago.

I was lucky enough to spend two days on the water and enjoy a number of awesome observations while trying to make sense of the explanations given by the interpretive guides in Japanese. Some of the most exceptional sightings were the groups of competing humpbacks, where males repeatedly slapped the surface with their fins, possibly to gain access to a female. I also observed a pod of spinner dolphins resting in one of the bays, far from the ocean swell. Furthermore, during my stay there, I managed to make about ten underwater sound recordings that I was eager to listen to and analyze once I returned home.

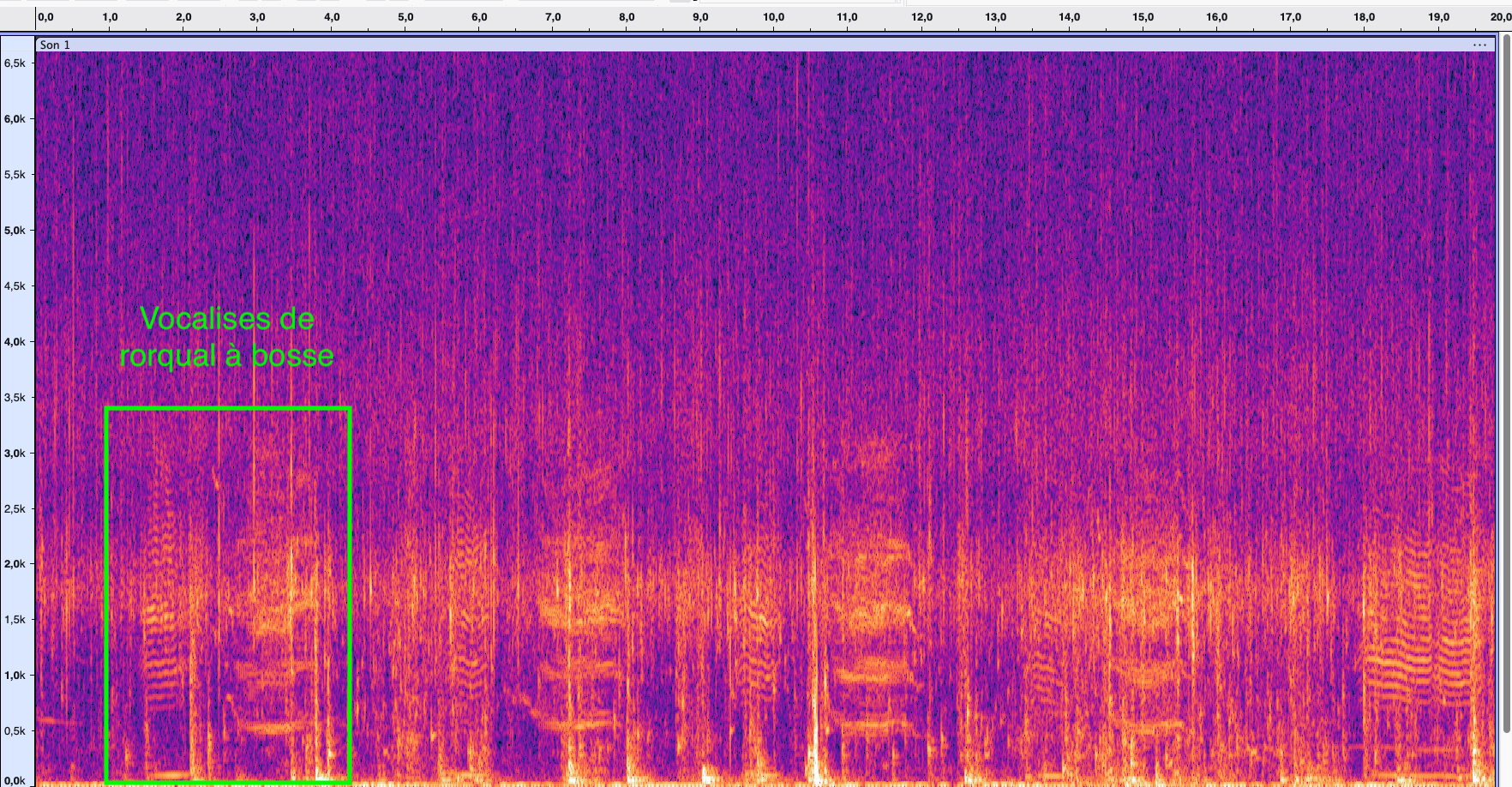

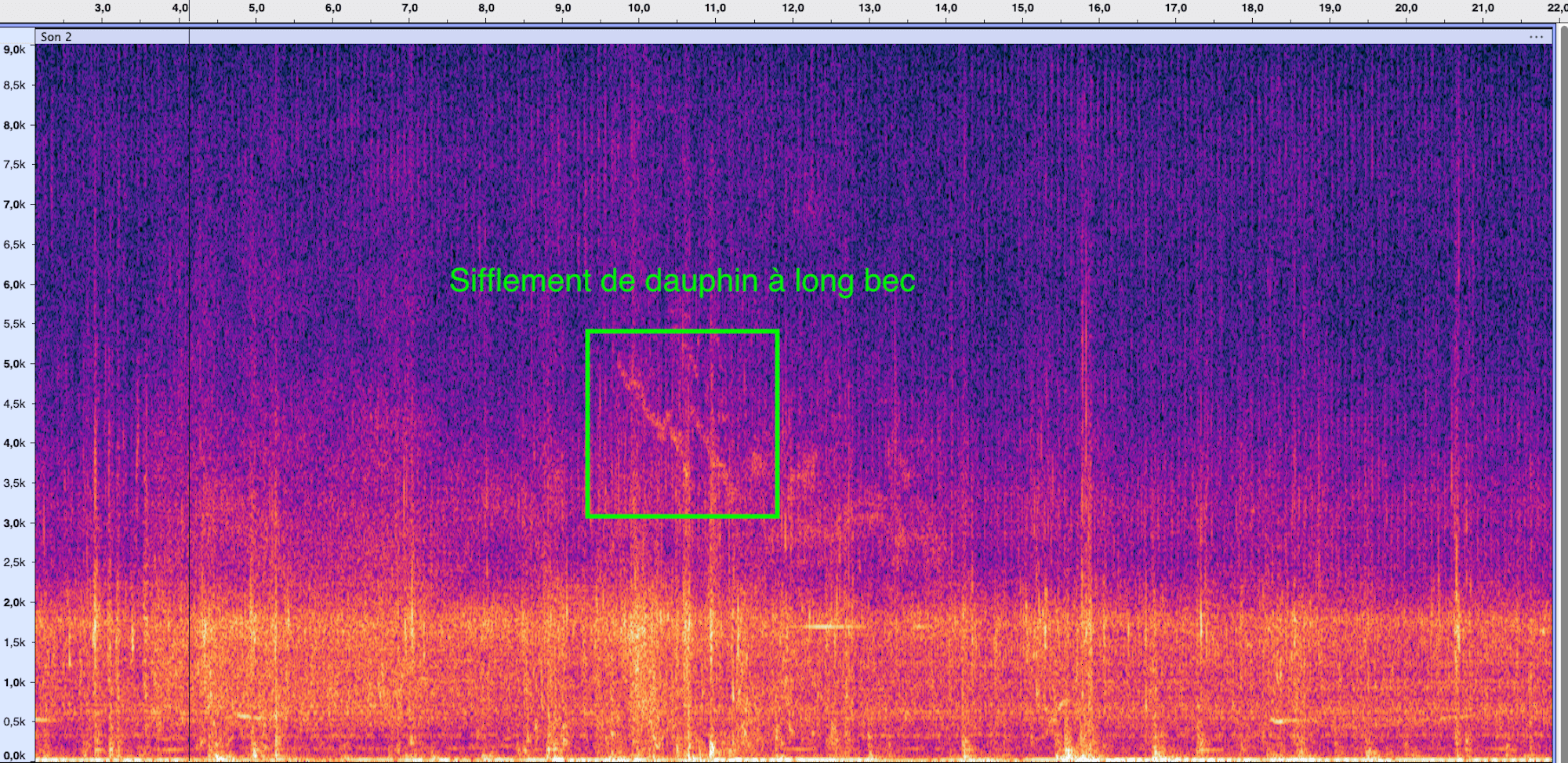

Departure from the archipelago and sound processing

The return trip was an adventure in itself. An adventure that involved leaving the small tropical archipelago of Ogasawara to travel to the St. Lawrence Valley, which was still covered in a beautiful blanket of snow. Back home, it’s time to eagerly review the audio files recorded in the Pacific. The sound recordings notably allow me to make two interesting observations about cetaceans. The first is that nearly all the files include the captivating songs of humpback whales as a backdrop. These sound sequences produced by males during the breeding season can be heard all around the archipelago, which is frequented for this very reason. The second, is that spinner dolphins are very silent when they are resting. Indeed, the recordings contained no echolocation clicks and very few whistles or other social vocalizations, especially considering the number of individuals observed. This information is corroborated by the scientific literature, which states that this species primarily relies on its vision to navigate when it is at rest. It is with these observations, a treasure trove of material for training and other projects, as well as some wonderful memories that the Ogasawara adventure comes to an end.

Whale-watching jargon in Japanese

鯨 – Kujira – Whale

ザトウクジラ – Zatou Kujira – Humpback whale

マッコウクジラ – Makkō Kujira – Sperm whale

イルカ – Iruka – Dolphin

ハシナガイルカ – Hashinaga Iruka – Spinner dolphin

シロイルカ – Shiro Iruka – Beluga (literally, “white dolphin”)

ブロー – Burō – Spout

海 – Umi – Sea

船 – Fune – Boat

Learn more :

- 1982) Tyack, P. et Whitehead, H. Male competition in large groups of wintering humpback whales. (États-Unis) Behaviour 83 : 132 – 154.

- (2003) Ichiki, S. Ecotourism in Ogasawara Islands. (Japon) Global Environmental Research 23 : 15 – 28.

- (2007) Aoki, K., Amano, M., Yoshioka, M., Mori, K., Tokuda, D. et Miyazaki, N. Diel diving behavior of sperm whales off Japan (Japan) Marine Ecology Progress Series 349 : 277 – 287.

- (2019) Lammers, M. O. Spinner Dolphins of Islands and Atolls (États-Unis) Ethology and Behavioral Ecology of Marine Mammals : 369 – 385.

- (2021) Broadening the Search for Whales, Dolphins, and Seabirds around the Mariana Archipelago. (États-Unis) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA).

- (2023) Tsuji, K., Mori, K., Suzuki, M. et Tsumaki, Y. First Sightings of Longman’s Beaked Whale (Indopacetus pacificus) off the Chichijima Islands, Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands, Japan. (Japan) Aquatic Mammals 24 (3) : 282 – 287.

- (2024) Humpback Whale. (États-Unis) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA).

- (2024) Whale penis extrusion & mating practices explained thanks to underwater footage of humpback whale’s penis. (États-Unis) Pacific Whale Foundation.

- (2025) Dolphin Watching and Swimming (Japan) Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism.

- (2025) Ogasawara Whale Watching Association. (Japan) Ogasawara Whale Watching Association.

- (2025) Sailing Schedules and Fares. (Japon) Ogasawara Kaiun Co., Ltd.

- (2025) Spinner Dolphin. (États-Unis) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA).

- (2025) クジラ イルカウォッチングウォッチングガイド. (Japon) Ogasawara Whale Watching Association.