A year-round resident of the St. Lawrence, the beluga inspires admiration. With their ever-smirky facial expressions, belugas have become one of the symbols of the fragility of the St. Lawrence for the citizens of Quebec. However, our relationship with and our views of this white whale have not always been positive… Let’s take a closer look at our connection with the St. Lawrence belugas throughout history!

Ancient presence

The origin of belugas in the St. Lawrence dates back over 10,000 years to the time when parts of Quebec were covered by the Champlain Sea. After the glaciers had melted, the retreating waters geographically separated the St. Lawrence beluga from the other populations that had returned to the Canadian Arctic.

Adhothuys a.k.a. white porpoise: a resource with many benefits

When did humans first start interacting with belugas in the St. Lawrence? Potentially 5,500 years ago. Beluga remains have been identified at the Lavoie aux Bergeronnes site, which at the time was used by First Nations mainly for hunting seals. These remains are believed to stem from the opportunistic harvesting of belugas. During the Middle Woodland period (approximately 2,400 to 1,000 years BCE), belugas were hunted by Iroquois communities. Then, in 1535, Europeans first encountered belugas during Jacques Cartier’s second voyage to the St. Lawrence. Hitherto referred to as adhothuys by the resident Iroquois, Europeans renamed this strange, unknown animal the “white porpoise.”

Thus, French Canadians began hunting belugas as a new resource to exploit in the 18th century. The animals’ fat and skin were used to make oil and leather, respectively. Fetching a good price on the markets, this trade led to the development of sedentary beluga fishing, especially in the Rivière-Ouelle sector where the animals were very abundant. In the years that followed, approximately 44 fishing sites were built and used until this activity finally came to an end in the 20th century.

From “white porpoise” to fishermen’s sworn enemy

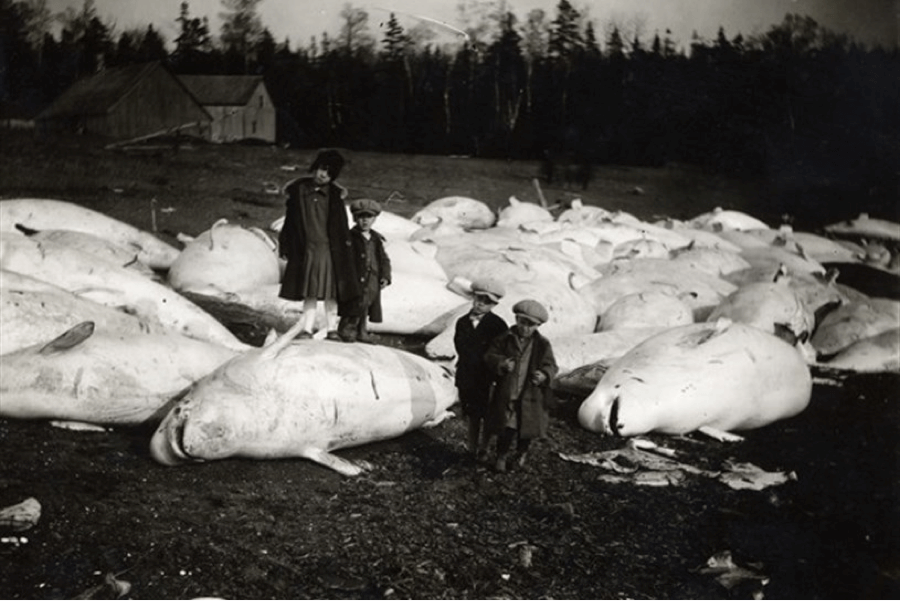

In 1928, cod were becoming rare in the St. Lawrence. Who was the culprit? The white porpoise! Fishers believed that a single beluga could consume nearly 45 kilos of fish per day and that the species was therefore responsible for declining cod stocks! Considering the species a harmful competitor for the fishing industry, the Quebec government therefore pulled out all the stops in its anti-beluga policies. Between 1932 and 1938, rifles were distributed to fishermen, who were offered a $15 bounty for every beluga tail they turned in.

In 1932, to eradicate these “evil” animals, bombings from seaplanes took place in a number of sectors of the St. Lawrence. At the time, the beluga population was estimated at nearly 100,000 individuals, meaning rifles would never be effective against such numbers! Today, in hindsight, we know that these estimates were incorrect and that the population must have been between 12,000 and 17,000 individuals at the end of the 19th century. Between 1932 and 1938, nearly 3,000 animals were slaughtered.

Beluga unjustly accused

In 1938, Quebec’s Department of Fisheries funded a study on the impact of belugas on commercial cod fishing. Researcher Vladim Vladykov was commissioned by the Department to study the stomach contents of 165 carcasses over the course of a year. The findings were unequivocal: belugas were not responsible for collapsing cod stocks! Moreover, it was shown that each beluga consumes a maximum of approximately 12 kilos of fish per day, and not around 40 as previously claimed. Thus, the nickname “insatiable giants” belugas had been given was unfounded. Vladykov’s research led to the end of commercial beluga hunting in the 1950s and efforts to exterminate the animals. However, recreational hunting of the species continued, with about ten or so belugas killed per year.

Population in peril, alarm bells sound

In 1973, Fisheries and Oceans Canada estimated the size of the beluga population for the first time. The verdict was in: there were just 500 individuals left in the St. Lawrence.

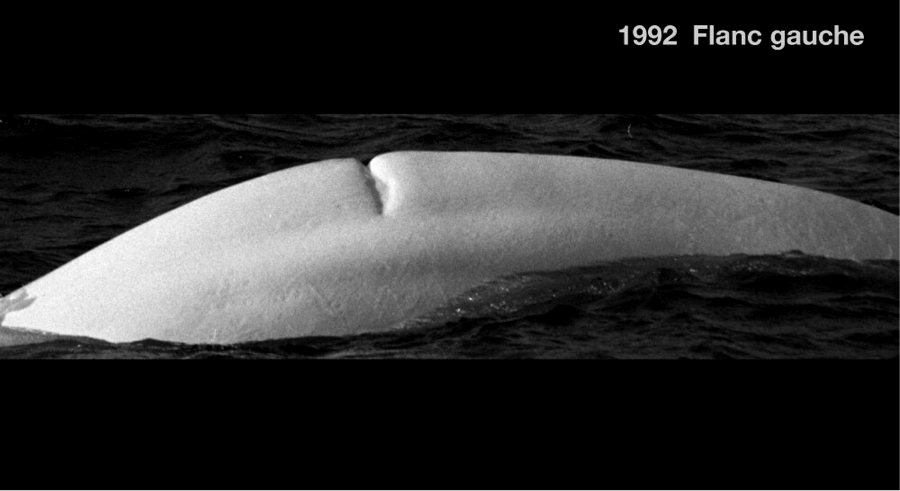

That same year, two journalists from Ontario, Leone Pippard and Heather Malcom, travelled to Quebec to follow researchers working on marine mammals. Unfortunately, a lack of financial support resulted in the project being cancelled at the last minute. As they had already arrived in Montréal, the two journalists decided to do their own report on marine mammals, and continued onward to Pointe-Noire to observe belugas for the entire summer. After countless hours of observing, they realized that they were able to recognize individuals passing through the mouth of the Saguenay! This observation led to the conclusion that the St. Lawrence beluga was not as plentiful as previously believed, and that action was urgently needed to protect them. Eager to sound the alarm on the St. Lawrence beluga, Leone Pippard continued her research and observations, becoming a pioneer in research on this iconic species.

Her work notably led to the banning of recreational beluga hunting in 1979. A carcass recovery program was also set up in 1982 to understand the impact of chemical pollution on belugas. Lastly, the creation of the Saguenay–St. Lawrence Marine Park in 1998 was also made possible thanks to Pippard’s work on the importance of the mouth of the Saguenay for belugas.

Co-existing with humans

With the first whale-watching cruises of the early 1980s, belugas gradually became the stars of the St. Lawrence. However, this species has been listed as endangered since 1983, and is a victim not only of its own popularity, but of human activities as well. Currently, the St. Lawrence population is estimated to number between 1,500 and 2,200 individuals. However, these figures do not correspond to an increase since the ban on hunting , but rather to an adjustment in our methods for counting these animals. The population is considered stable but is struggling to bounce back; the aforementioned figures correspond to just over 10% of the numbers estimated in 1865.

Factors limiting the beluga’s recovery include contamination by toxic substances, disturbance by maritime traffic and global warming. Although the relationship between humans and belugas has not always been harmonious, it is now our collective duty to protect them, raise awareness of their importance and ensure their future in a healthy, well-preserved environment.

Pour en savoir plus

- Alan Frank. 2008. Les pêcheries de l’estuaire et la guerre aux marsouins. Histoire maritime, Escale Nautique.

- Pierre Béland. 1996. Les bélugas ou l'adieu aux baleines. Libre Expression