Long before the whales that we know and love roamed the seas of the planet, many different creatures lurked in their depths. Millions of years ago, our oceans would have looked entirely different. Join me as we travel through time and unravel the mysteries of prehistoric whales.

Evolution

Whales have been around for about 50 million years, long before humans ever walked the Earth (between 6 and 2 million years ago). Modern whales only appeared about 34 million years ago. With that much time on their hands (or fins, if you prefer), it’s no wonder they were able to expand their ranges and diversify. The whales we know today aren’t the same ones that existed millions of years ago. As the oceans and temperatures change, lands drift apart and old habitats dry out, many of the prehistoric species become lost to time, a phenomenon also common in land animals.

The extinction of old species also gives rise to new ones that are better suited to their environments.

Phiomicetus anubis, le dieu de la mort

Belonging to the extinct genus Protocetid, a group of semiaquatic aquatic mammals from the Eocene, Phiomicetus anubis, is believed to have lived approximately 55.8 to 33.9 million years ago. The fossil was found near the UNESCO World Heritage Site Wadi Al-Hitan, or “Valley of the Whales.” Its name pays tribute to Anubis, the ancient Egyptian god of death with the head of a jackal. The name was chosen because of the similarity of the specimen’s skull to that of modern canids.

The 2021 study describes one distinctive feature of this new genus, namely the teeth, which resemble those of modern pinnipeds. After observation, it was found that their teeth were used for capturing prey and feeding on armoured fish, turtles and sharks. They may have used a hunting technique similar to that of crocodiles, pulling them onto land and tearing them apart by twisting their bodies.

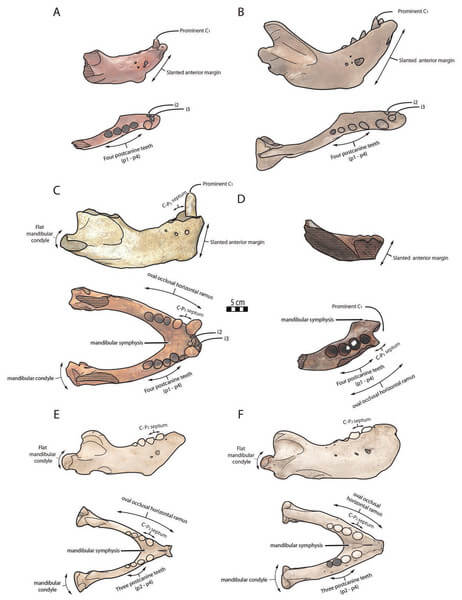

Ontocetus posti, an extinct walrus

By examining a pair of fossilized jaws from the Early Pleistocene of the United Kingdom and a fragmentary jaw from the Late Pliocene of Belgium, researchers were able to describe a new species of Ontocetus, an extinct genus of walrus. The specimens resembled that of other Ontocetus species with four post-canine teeth, a lower canine larger than the cheek teeth and a lower incisor, amongst other traits. However, many traits, like the fused and short mandibular symphysis and the short distance between the canine and cheek teeth, are usually found in Odobenus.

This ancient walrus existed somewhere between 3.7 and 1.7 million years ago in Europe. The findings, from a study published in 2024, suggest that the species specialized in suction feeding, similar to modern walruses. This evidence suggests that they filled a similar ecological role to modern walruses. Their diet likely consisted of clams and other molluscs.

The global cooling in the Pleistocene caused the ice sheet to expand and the O. posti to become extinct around 1.7 million years ago. Trapped in the North Sea basin with a restrictive diet made it unable to tolerate the abrupt effects of climate changes occurring during the Early Pleistocene.

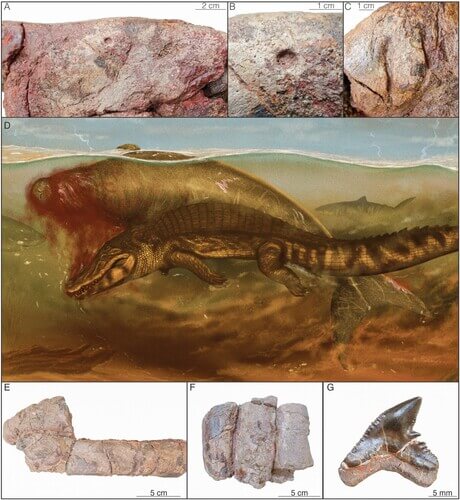

Culebratherium sp., the sea cow that can’t catch a break

A sirenian specimen dating back to the Early Miocene (23 million to 16 million years ago) was uncovered in 2019 in the Agua Clara Formation, in Venezuela. The fossils were identified as a dugongine sirenian, i.e. related to dugongs and manatees.

The 2023 study found that the fossil, belonging to the Culebratherium genus, presented predation marks from not one, but two different predators: a tiger shark (Galeocerdo aduncus) and a crocodile. The study explains that this specimen is important as it gives insight into the trophic interactions of important predators. The markings from two different carnivores show the importance of sirenians in the food chain of the Caribbean during the Cenozoic.

The marks left by both predators are mostly concentrated around the snout, probably in an attempt to suffocate their prey. Marks of a “crocodile death roll,” a technique used by modern crocodiles, support these claims.

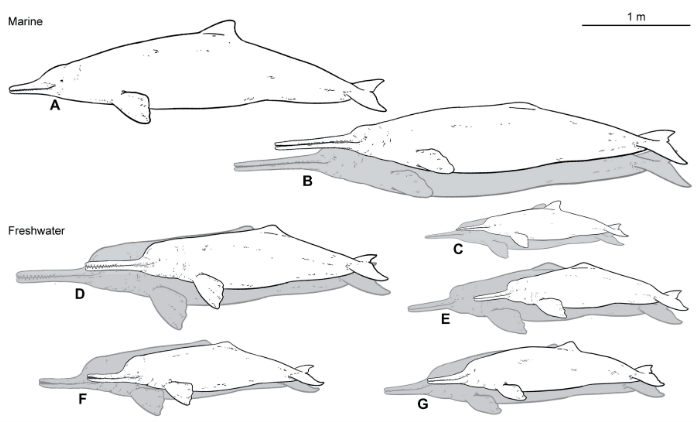

Pebanista yacuruna, A large river dolphin

Many dolphin lineages evolved separately to life in fresh water, including river dolphins in South Asia and the Amazon. Long before these species emerged, however, lived the largest freshwater dolphin ever recorded.

Measuring an estimated 3.5 metres long, this newly discovered species is the largest odontocete (toothed whale) to invade freshwater systems. A 2024 study explains that their size is believed to be an indication of the vast resource availability in the waters they inhabit, also supported by other taxa from that period. Another theory is that their size has to do with the lack of predators and competitors in wetlands.

This “new” dolphin is part of Platanistidae, a family of freshwater river dolphins with the only two extant species being the Ganges river dolphin and the Indus river dolphin (bhulan). This family of dolphins grew more diverse between the Oligocene and the Early Miocene during the global cooling event. Pebanista’s presence in Peru confirms that plastanistids were present in South America and were similar in size to the other marine relatives of the time.

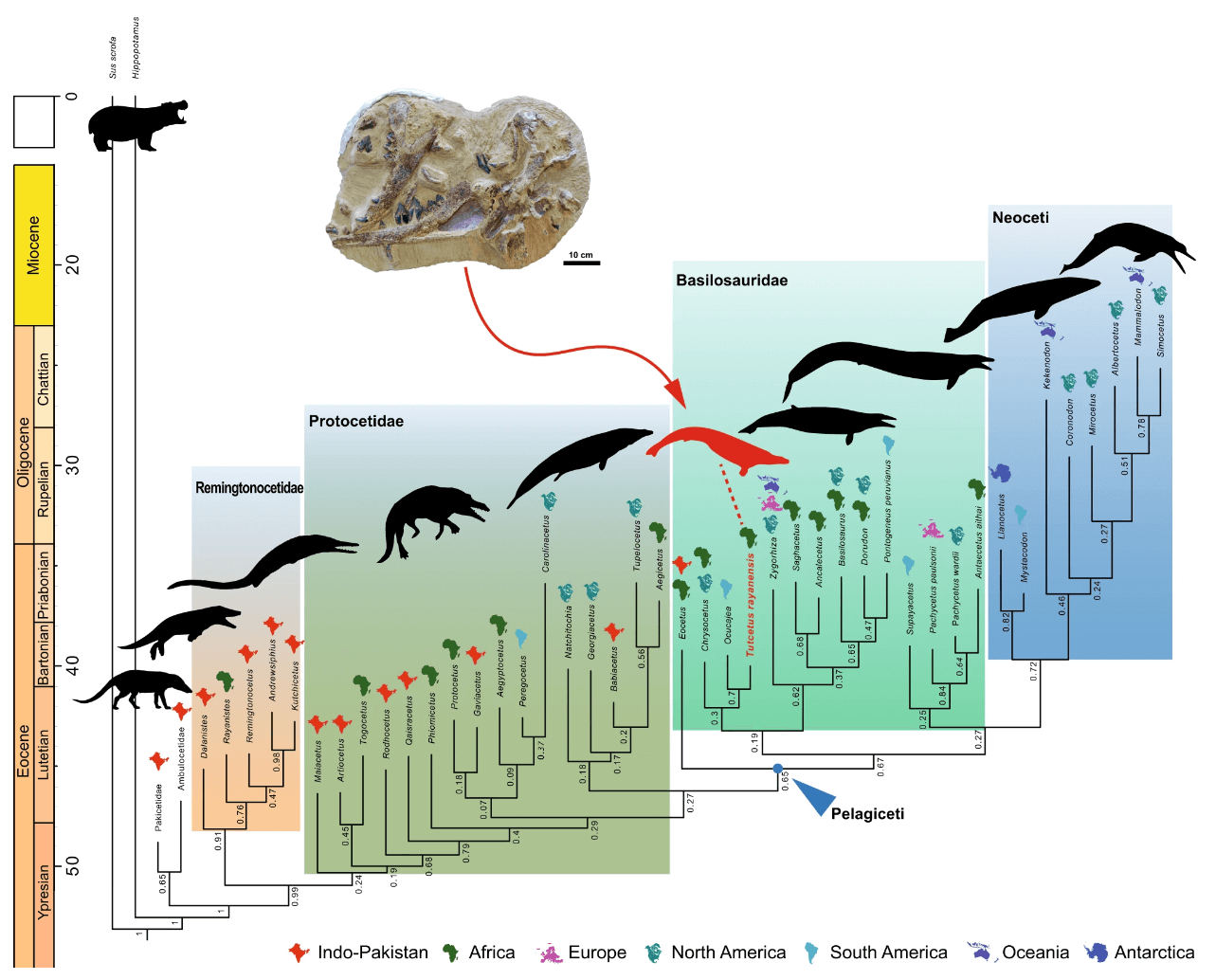

Tutcetus rayanensis, the oldest of its family

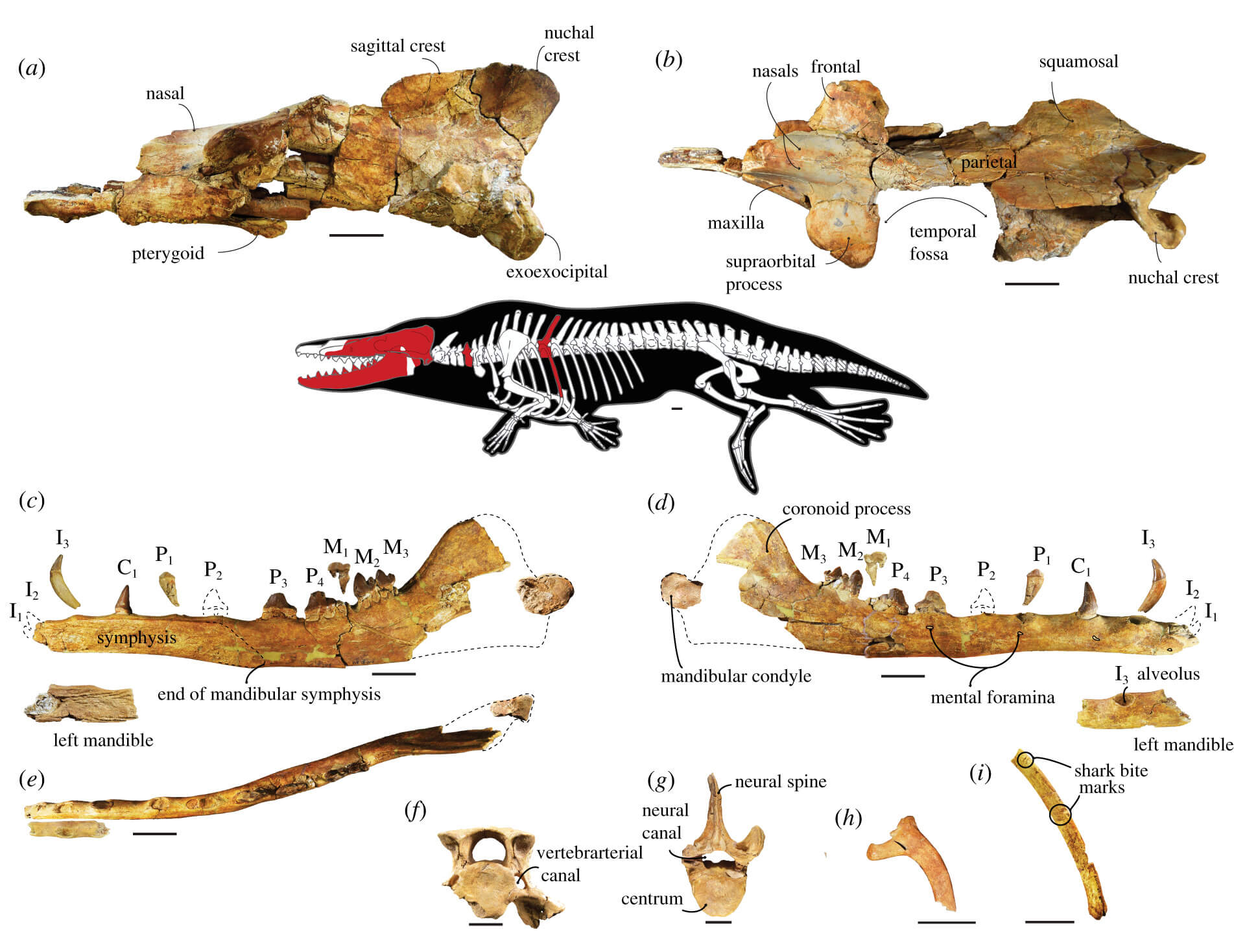

A study published in 2023, describes a new species from the extinct Basilosauridae family. Tutcetus rayanensis is the smallest known whale on the African continent, measuring 2.5 metres long and weighing about 187 kg, but was essential in expanding the known range of basilosaurids. It is also one of the oldest whale records in the world, dating back to the middle Eocene (approximately 41 million years ago).

After dental analysis, it was discovered that the specimen was near adulthood, as it was not yet sexually mature. Rapid dental development coupled with its large size suggests a fast-paced life for Tutcetus. The location of the specimen also suggests that this was a calving ground, that the juvenile mortality rate was low, and that the species likely had just one offspring a year.

More to uncover

Though many extinct species were discussed in this short article, there are still many others that were not described herein and even more waiting to be discovered below the surface. With every new finding, our understanding of prehistoric oceans becomes clearer, but the list of remaining questions grows ever longer. Will we ever truly understand the mysteries of the ocean depths?