How do we know whether or not the whales of the St. Lawrence are doing well? This is the mission that the Sept-Îles Education and Research Centre (CERSI) has undertaken by assessing the individual well-being of fin whales and humpbacks in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. According to preliminary results, there appears to be a correlation between cetaceans with anthropogenic lesions and their ability to maintain good physical condition.

Carried out as part of a larger project, this study aims to analyze improvements or deteriorations in body condition that reflect the state of the nutritional reserves in these individuals. This would pave the way to carry out population modelling and make recommendations for the protection of cetaceans in the St. Lawrence.

Touching with your eyes!

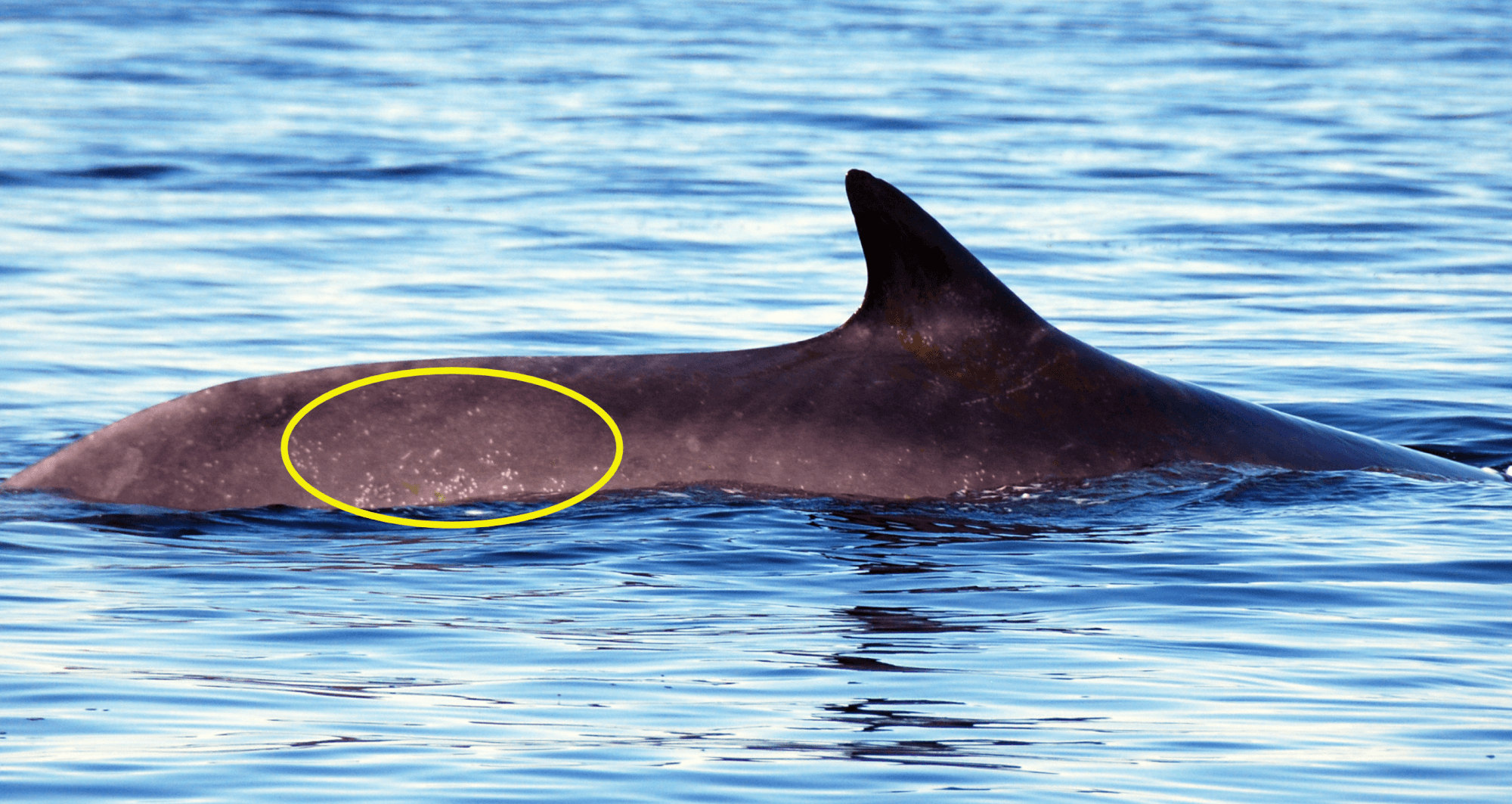

Between 2016 and 2020, Anik Boileau, a scientist specializing in animal welfare sciences (ethology and veterinary sciences) and director of CERSI, assessed the well-being and physical health of 50 humpback whales and 50 fin whales in order to validate an indicator of health and physical well-being in cetaceans observed in the Sept-Îles region. Over 6,400 photographs of the dorsal and caudal regions of large rorquals were taken to analyze four health indicators :

1) Body condition (fat levels which reflect nutritional stocks)

2) Overall skin health: viral, bacteriological, and fungal diseases;

3) Presence of epibionts (such as diatoms or barnacles) and parasites (presence or scars from cookie-cutter shark or lamprey).

4) Injuries of anthropogenic origin (physical trauma caused by human activities such as entanglement or collision) or other animal species (e.g. killer whales).

This first step validates the methodology used for assessing the health state and physical well-being of these whales. This will be useful for the rest of the well-being assessment protocol, which will include other data such as stress levels and the microbiota contained in the vapours of the whale’s blow.

Minimizing stress

Anik Boileau’s watchword: to be the least invasive possible in order to take into account the animal’s individual well-being. This is made possible with remote data collection methods such as the use of powerful cameras, infrared cameras to measure the animal’s blowhole temperature, and 5-metre-long poles to collect breath samples in six Petri dishes attached with Velcro. It’s no easy task studying giants when you’re out in the open sea!

A wealth of information for the naked eye!

Based on statistical correlations, Anik Boileau and her team concluded that each animal showing entanglement or collision lesions also had a thinner body condition.

“Whales that have had more significant injuries are more likely to be slimmer, even once these wounds have fully healed,” explains Anik Boileau, “This physical trauma may have generated chronic stress, which means that the rorquals are unable to maintain an optimal body condition.”

The animals studied that did not show any anthropogenic lesions were in optimal body condition.

As for skin diseases, 68% of the humpbacks studied were affected by skin nodules, i.e. small, well-defined bumps of normal or greyish colour. Approximately 56% of humpback whales showed hypo-pigmented skin patch syndrome, with areas on the body ranging from opaque to translucent. Pale focal disease , which is observed as a cluster of small white or grey lesions, was present in 56% of fin whales and 48% of humpbacks. Dark focal disease consisting of round, dark skin lesions was observed in 32% of fin whales and 16% of humpbacks.

Epibionts (organisms that use whales as a substrate such as diatoms and barnacles) and parasites such as lampreys and cookie-cutter sharks (small flesh-eating fish) have an impact on skin health and skin diseases. On the other hand, they do not seem to have any considerable effect on the animal’s body condition.

The CERSI team also established a new term for previously undocumented lesions: cutaneous papules. Resembling an allergic reaction, these papules are found in 16% of humpback whales, compared to only 2% of fin whales!

An approach that gives us food for thought

The study is innovative in that it complements the traditional approach to conservation in Quebec. It is the first study in the St. Lawrence to be carried out at the level of skin lesion analysis, and more importantly, the first one to link these indicators with an individual’s state of health, notably the relationship between human-caused injuries and the animal’s body condition.

For Anik Boileau, the negative impact of human activities and the climate change that may be caused by such activities leads to an ethical reflection on how we conduct research: The question then becomes what research can do at an individual level rather than just at the population level. “Perhaps this could allow us to anticipate and “raise a red flag” in terms of laws and protection for humpbacks?” adds Anik.

Rethinking protection?

The humpback whale is not a threatened species in Quebec, as the North Atlantic population is doing well. However, if animals that survive an entanglement or collision suffer reduced body condition due to chronic stress, this could have an impact on their reproductive success and long-term consequences for the population.

And even more to come!

Anik Boileau’s article will be published in English later this year in the journal Animals. Anik points out that this study is just the first step of a project that will assess the well-being of whales over time. The study was limited to a small number of individuals and presents starting point data. This project will help paint a better portrait of the large rorqual population in the St. Lawrence. In addition to the animals’ body conditions and skin lesions, the project will take into account a behavioural indicator as well as physiological parameters such as body temperature, hormone levels, and microbiota composition.

Boileau collaborated with Happy Whale as well as with the MICS for this study. Data sharing between research centres, such as sharing photo-identifications of individuals, could be very useful for monitoring the state of health of those whales that come visit us year after year!