Feeding

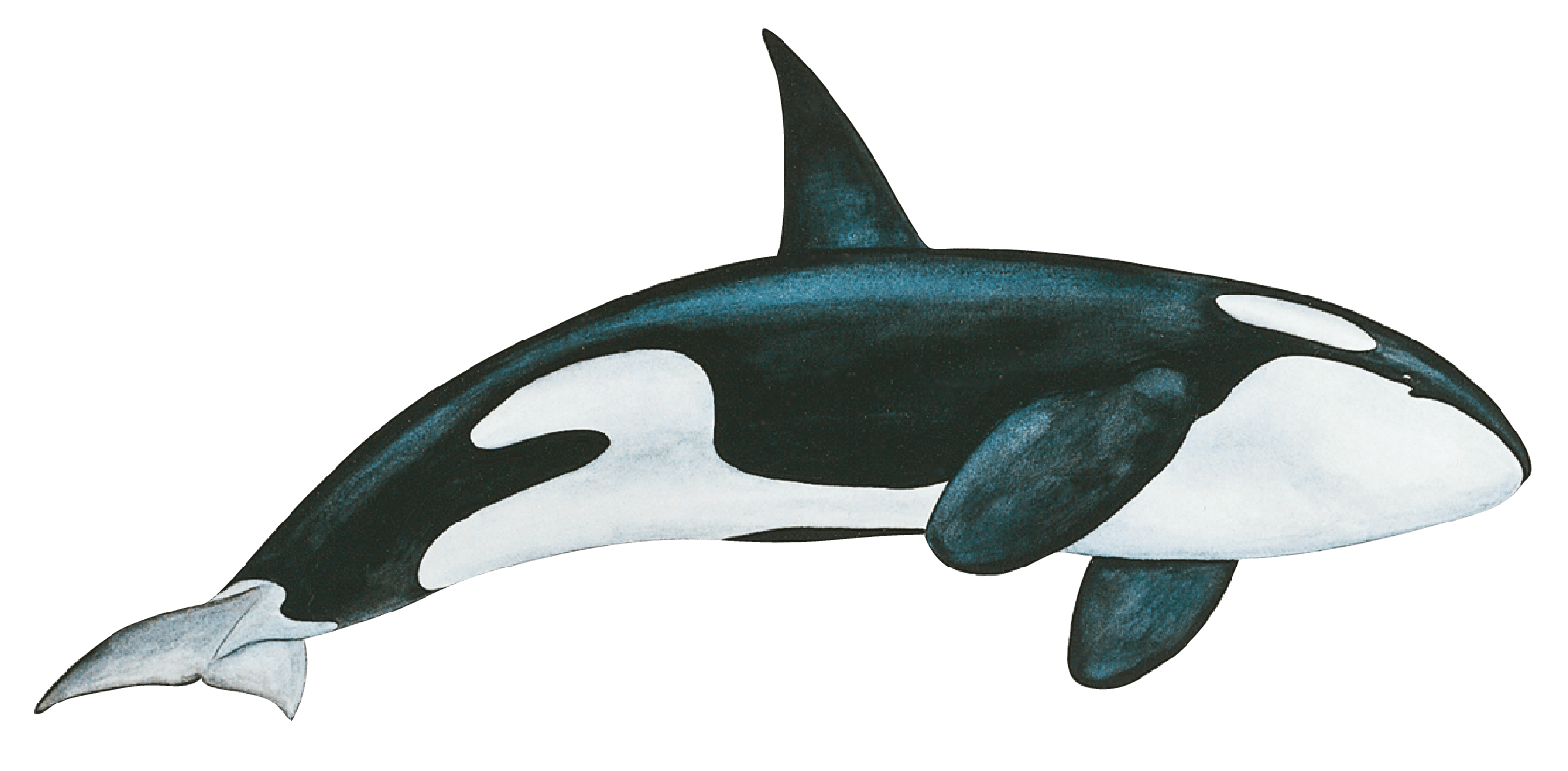

Killer whales have a highly varied diet, feeding on small schooling fish, squid, turtles, seals, seabirds, sharks, and rays, but also large rorquals and sperm whales. Occasionally, they’ll even take a deer or moose that they catch as the latter are swimming across a channel. Within their family units, killer whales develop highly orchestrated hunting strategies that allow them to attack much larger prey, earning them the nickname of “sea wolf”. Group members cooperate to harass and herd their prey like a pack of wolves or a pride of lions. They dislodge seals from their ice floes and even beach themselves to capture some of their prey. These hunting strategies are transferred from adults to the young through learning. Depending on the location, killer whales are either very specialized, feeding exclusively on salmon or marine mammals for example, or highly adaptable to the type of prey available.

On the surface

The killer whale is a rather fast and energetic swimmer, and can reach speeds of 45 km/h when chasing prey. Like all dolphins, it is capable of aerial behaviours and exuberant leaps: it porpoises and surfs on the waves, can leap and lift its body entirely out of the water (full breach) to land on its back or belly, slaps the water surface with its tail and fins, spyhops by holding its head above the water and its body straight down to the pectoral fins, and can even swim backwards.

Diving

The diving behaviour and abilities of the killer whale are poorly documented. Most of its dives seem to be within 20 m of the surface, although they may exceed 100 m. Dive times are rather short (between 4 and 10 minutes) but can reach up to 20 minutes.

Social

Killer whales can be observed alone or in groups. For killer whales inhabiting the North Atlantic, little is known due to their low numbers, dispersion and nomadic ways. In the Pacific, which supports a resident population of some 300 individuals, killer whales live in stable matriarchal units that can comprise 2 to 3 dozen individuals.

Vocalization

From a vocalization perspective, the killer whale is very active. Its repertoire is vast: squeals, whistles, grunts, cries and clicks for echolocation. Each family unit has its own dialect, which is used for communication between members and for group cohesion.