It is estimated that 300,000 whales, dolphins and porpoises die globally from entanglement every year. Disentanglement efforts have had little effect on this figure. In an interview with Whales Online, Moira Brown and Mackie Greene of the Campobello Whale Rescue Team outline some suggestions to prevent entanglements.

Prevention better than cure

The best way to protect whales is to prevent entanglements from occurring in the first place. Protecting critical habitats and enforcing fishing and shipping regulations are important factors.

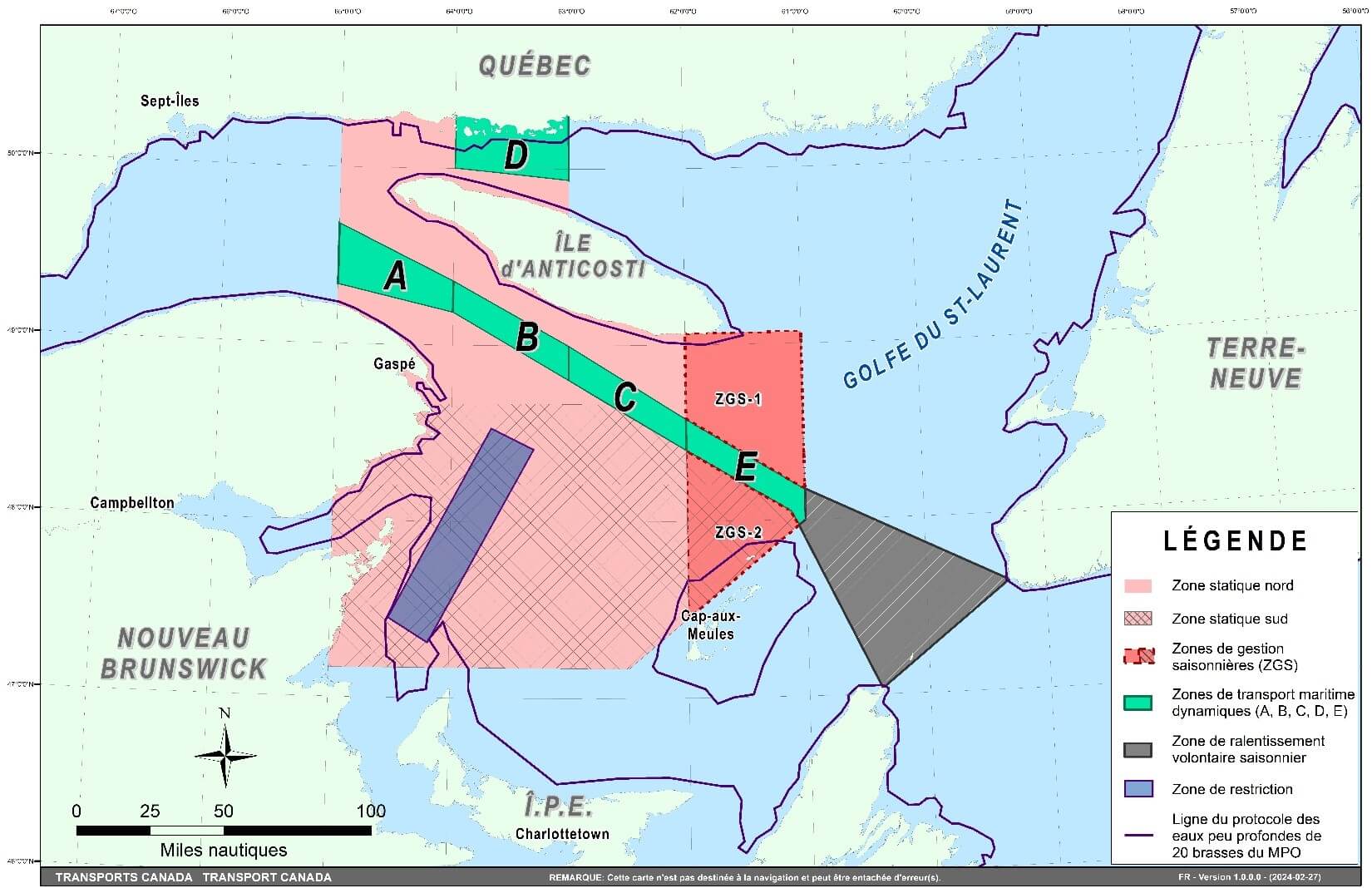

Canada employs adaptive fishery closure protocols such as seasonal and dynamic area closures when right whales are detected visually or acoustically. The law also requires that lost fishing gear, such as ropes, traps, and nets, be reported immediately to Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). This reporting program is unique to Canada. To reduce the risk of vessel collisions with right whales, Transport Canada implements speed restrictions when right whales are detected visually or acoustically.

The ideal solution to avoid clashes between the fishing industries and migrating whales is to avoid overlapping seasons. “The biggest part of the fishing [in the Bay of Fundy] takes place when whales aren’t here, [the lobster fishery] only starting each year in early November. That’s one of the greatest prevention measures right there,” explains Mackie Greene. In the Gulf of St. Lawrence, on the other hand, the fishing season partly overlaps with right whale use, as the whales arrive in late April and early May. To help reduce the overlap between fishing and whales, one of the measures has consisted of deploying icebreakers to Shippagan to allow the snow crabbing season to start earlier. Getting the fishing boats out on the water as early as possible minimizes overlap with the period when right whales are in the southern Gulf. Fishers can catch their quota and get their traps out of the water earlier, before the whales arrive, and thus prevent the occurrence of entanglements.

Every year, the DFO releases its protection measures. Such measures, which come into effect in late April, include acoustic and visual surveillance, which can result in a 15-day ban on gear. Fishers have at least 48 hours to remove their gear, longer if weather conditions are severe. If right whales persist in an area, then DFO closes the area to fishing with ropes for the remainder of the season, i.e. until November 15.

All tangled up

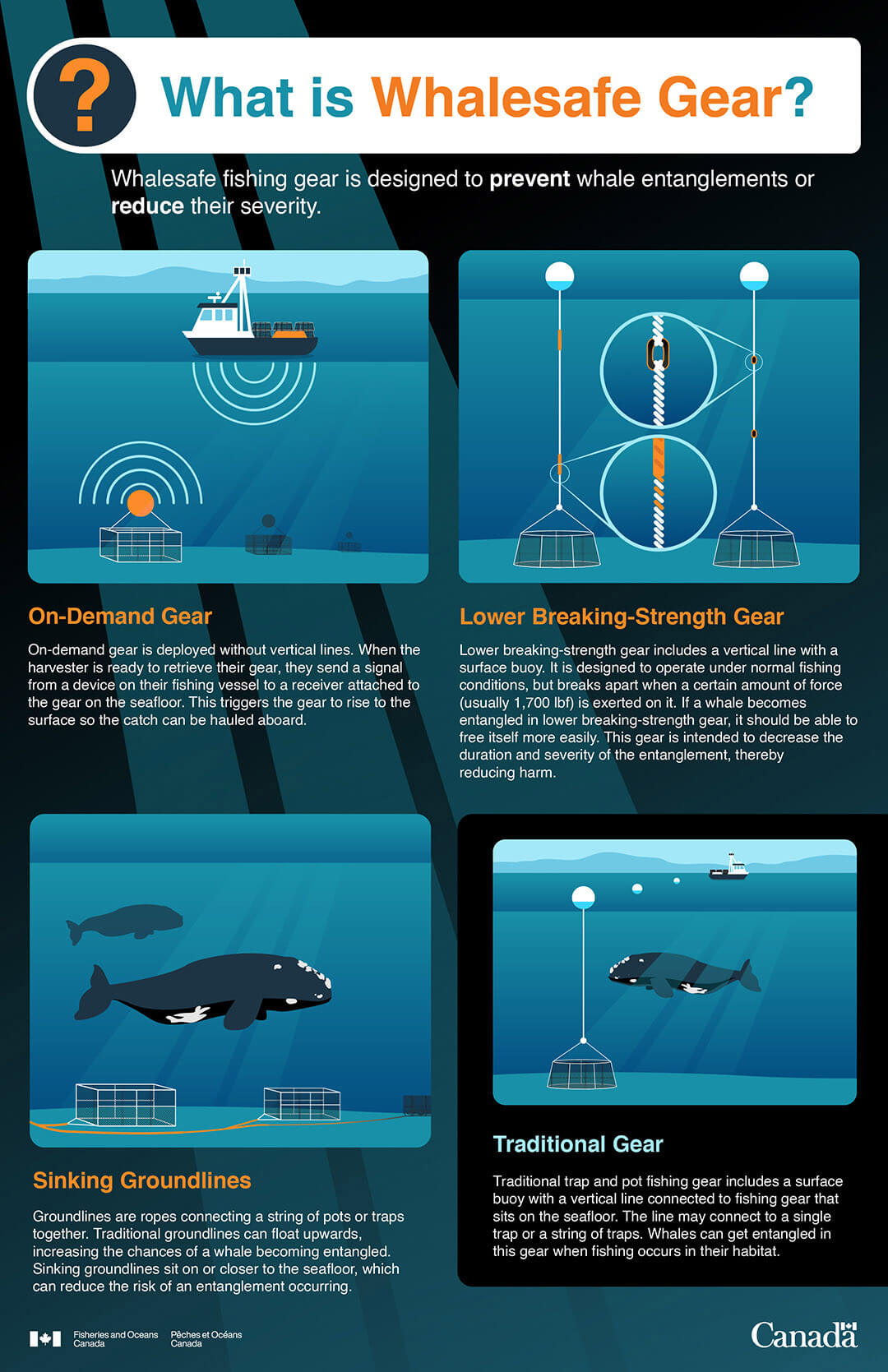

The main issue with entanglements is the rope. If less rope were present, or if it weren’t in the water column, it would be less of an issue.

The DFO is working with the fishing industry, Indigenous and non Indigenous groups, to investigate the use of low breaking-strength rope or links that can snap at 1,700 pounds of force. The hypothesis is that if a whale were to drag one of these ropes along, the rope would break, leaving the traps behind.. Such rope is being tested in lobster fisheries in the Gaspésie region as well as in Prince Edward Island to ensure that it is safe and practical for fishers to use. Another solution under consideration and trial use is rope on demand, or ropeless gear technology, i.e. gear without vertical lines that is only triggered from the fishing boat when the latter is nearby and ready to retrieve its trap. Rope on demand equipment has been tested, a technology selected for use in water and used with an experimental fishing license in the snow crab fishery in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Retrieval programs

In Canada, fishers are required to mark their gear with ID numbers and install colour-coded marks on their rope, which are useful for accountability. Unique to Canada is the reporting of lost fishing gear, itis required by law. However, not just anyone can retrieve the gear. All retrieval activities require a licence under Section 52 of the Fishery (General) Regulations. Programs have been in place in t he past few years for permitted fishers to haul a lost buoy. “Fishers are not normally allowed to haul someone else’s gear. They can’t even haul their own gear after the snow crab season is over,” explains Moira Brown. The Ghost Gear Fund encourages non-profits, Indigenous communities and non indigenous fishers, and government agencies to apply for funding, receive basic training and, most importantly, remove all abandoned, lost and otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG). Gear retrieval projects exist all along the coast but are most concentrated around the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

“You might wonder, ‘How can you lose your gear?’ but it’s a buoy at the surface. You can’t see it from far away. And if it does get moved from storms, it’s hard to find it. And, sometimes with the tides, the buoy will get caught down, and two or three days later, it’ll pop back up,” explain Moira Brown and Mackie Greene.

Right whales get entangled not only in active gear but also in ghost gear – lost, discarded or abandoned fishing gear – that remains at the surface or caught at the bottom. Smart Buoys, like the ones produced by Blue Ocean Gear, have embedded trackers that allow for quicker retrieval. Gear can be tracked using a GPS signal that can be seen on an app on one’s phone, which allows it to be retrieved more easily. Smart buoys have been used in fisheries, aquaculture and research.

Other species caught in the crossfire

Entanglement is a problem that affects more than just the right whales; other marine mammals and aquatic species are also impacted by nets and ropes floating in the ocean. Other species prone to entanglement include turtles, sharks and rays.

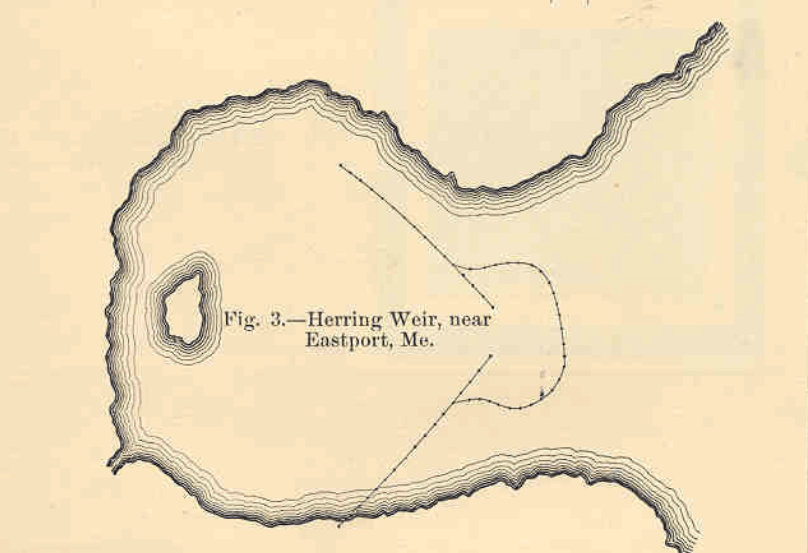

The CWRT also responds to calls about humpbacks, minkes, fin whales, and even leatherback turtles (a species at risk). “It’s mostly right whales, but we don’t care. If it’s a whale entangled or anything really, any marine animal, we’ll try to help it the best we can,” explains Mackie Green. In a recent mission, the team rescued a minke whale that was entrapped in a herring weir. This happens when they chase their prey and swim into the trap. The shore-side exit opens toward shallow water, which they don’t like. By working with the fisherman, the CWRT provides advice on dropping the nets to the offshore side and cutting a few top poles so that the whale can exit on its own at high tide.

Hope for the future

As director of the CWRT, Mackie Greene hopes to be put out of business one day. His dream that whales and fishermen can live together is one that should be shared and may not be so unreachable after all. His hope for the future is that whales survive and that future generations can enjoy their presence.