From Matane and Bonaventure, Quebec to Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, belugas seem to be everywhere this spring. Since the start of the year, the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network (QMMERN) has identified around ten cases of belugas outside their normal range, both in Quebec and in the Maritimes. Although vagrant belugas keep the QMMERN busy at the start of every season, the number of cases is particularly high this year.

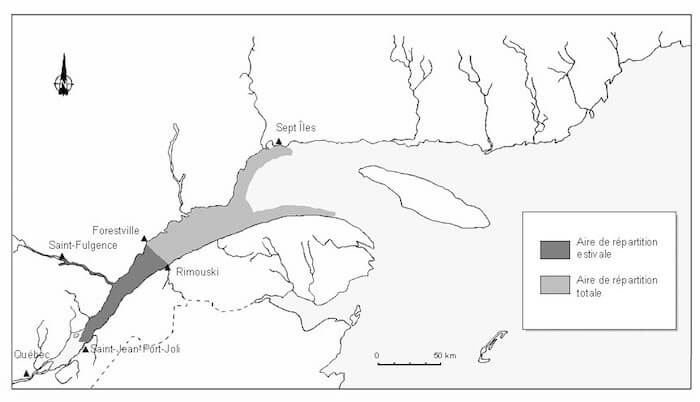

In summer, belugas are normally found in the upper Estuary, upstream of Forestville on the north shore and Rimouski on the south shore. So when a beluga is observed in the Gaspé or any farther east in the middle of June, it means that it is very far from its family.

Thus, in addition to being in unusual places, belugas outside the area are often solitary, which worries QMMERN experts. Indeed, when isolated from their peers, gregarious-by-nature belugas tend to develop sociable behaviours with objects or humans, which makes them more vulnerable to accidents. For example, a beluga that repeatedly interacts with boat propellers in a harbour may let down its guard and no longer perceive the danger normally associated with moving boats. This is why it is important to give the beluga its space and not interact with it, in order to increase the chances that it will find other members of its species.

Additionally, these wandering belugas sometimes develop a routine and an attachment to a port or marina. Over time, they therefore become less and less inclined to leave and their troubling stay is extended. This is the case of a beluga that lingered in the port of Matane for almost a month. First observed in late May, it was seen almost every day thereafter by QMMERN volunteers and fishermen. Fortunately, it ultimately left on his own!

Why do some belugas venture so far?

Belugas aren’t the only whales to roam widely. The many stories of stray whales show that these situations are not altogether abnormal.

In the case of the beluga in Matane, it may have splintered off from its group during the latter’s spring migration from the Gulf to the Estuary. Certain belugas also seem to have an exploratory character, which would explain their presence in the Maritimes.

And if these nomadic belugas stay in their new home, it may be because they are finding food there. Indeed, several of the vagrant belugas identified this spring have been observed hunting and feeding. Moreover, when they settle in a port or a marina, they manage to fill their need for interaction, which might compensate for the absence of the numerous social contacts they would normally have with their peers. However, these interactions with humans compromise the safety of the animal, which could be tempted to prolong its stay and thereby increase the risk of collisions.

How should I act in the presence of a beluga?

If you want to see a beluga, opt for a land-based observation spot rather than watching it from a boat. Take the opportunity to observe its different types of behaviour such as foraging, resting and playing.

“It’s a real challenge on the water: sometimes it’s the beluga that seeks interaction, approaching kayakers for example,” explains QMMERN coordinator Robert Michaud. In order to ensure the beluga’s safety, boaters and fishermen must resist the temptation to interact with the animal.

If the beluga approaches your boat, wait until you are a safe distance away and carefully leave the area. Under the Marine Mammal Regulations, all boats must maintain a distance of at least 100 metres from a beluga. In the St. Lawrence Estuary, however, the regulatory distance is actually 400 metres.

Response measures for vagrant belugas

For belugas outside their normal range, response options are rather limited. Most often, the QMMERN focuses on outreach: by informing the local population of the beluga’s presence and the importance of keeping a safe distance, the length of the animal’s stay and the risk of accidents are potentially reduced. For example, in mid-June, when a beluga took up residence in the barachois of the Bonaventure River, a popular spot with boaters and fishermen, the QMMERN mobile team went to meet with nearly a dozen organizations and businesses and 70 local residents. Informative posters were put up throughout the area.

At the Marine Mammal Emergencies call centre, operators also passed along several awareness-raising messages to residents concerned about seeing a beluga in their region. If you observe a beluga in an unusual location, contact Marine Mammal Emergencies at 1-877-722-5346.

This year, stray belugas in the Maritimes were a hot topic in the local media. Every radio interview is therefore an opportunity for QMMERN coordinator Robert Michaud to stress the importance of refraining from interacting with belugas.

The QMMERN relies on a network of volunteers, who are its eyes and ears on the ground. Volunteers diligently document the behaviour and state of health of vagrant belugas in Quebec waters. By sharing their observations, proactive companies and organizations also become valuable collaborators. Thus, the QMMERN and its partners are quickly notified of any change in the situation, which allows them to make the most well-informed decisions.

In the past, the QMMERN has already attempted a number of scare tactics to encourage a beluga to leave a busy area. Increased boating traffic posed an imminent threat to the safety of the beluga, which did not seem inclined to leave the area on its own. Ultimately, the intervention was unsuccessful, which is testimony to the difficulty in influencing the behaviour of wild animals, which are free to move around as they wish.

In some cases, the QMMERN and its partners may consider relocating a lost animal, as was the case with Nepi, a beluga that got itself trapped in the Nepisiguit River in 2017 (in French). These rescue operations are not without risk for both the animal and the ecosystem, which is why experts must ask themselves many questions before deciding to undertake them. In a future article, Whales Online will take a look at the various conservation and ethical issues associated with interventions intended to “help” animals in difficulty.