This week, we are giving the floor to Alexandre Bernier-Graveline, UQAM Master’s candidate in bioaccumulation and the effects of environmental contaminants on the beluga population of the St. Lawrence Estuary, studying under the direction of Jonathan Verreault. For the past two weeks, he has joined us at sea to take fat samples from biopsies.

We’re already well into September and it’s getting colder in Tadoussac, but that does not prevent my Master’s project from moving forward. The start of my project finds me sailing aboard the Bleuvet in search of belugas in the turbid waters of the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park. My goal is simple: to better understand the impact of chemical pollution on the beluga population of the St. Lawrence Estuary. Yet it will take me two years of reading, studying, analyzing, writing, reviewing and collaborating to get a clearer picture of things.

The interest of my project is specific to beluga fat. This fatty mass is actually a mixture of many fatty acids (molecules of variable length composed mainly of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen) that combine to form adipose tissue, i.e. energy reserves. It is assumed that the animal might potentially be able to adapt its metabolism to the contaminants it takes into its body by exchanging certain fatty acids for others and in this way cope with the changes brought about by pollution.

My collaboration with the GREMM allows me to join their research team in order to collect skin and fat samples through biopsies. In order to do this, we need to identify a group of belugas, approach them and then photograph individuals with conspicuous and persistent markings, scars or deformities that will allow us to easily identify and recognize them over the years. Everything hinges on this very moment: the boat is positioned parallel to the groups, and direction, distance and a constant speed must be maintained in order to keep up with the target individual. The beluga quickly dives then resurfaces and, as soon as it appears, the dart is fired.

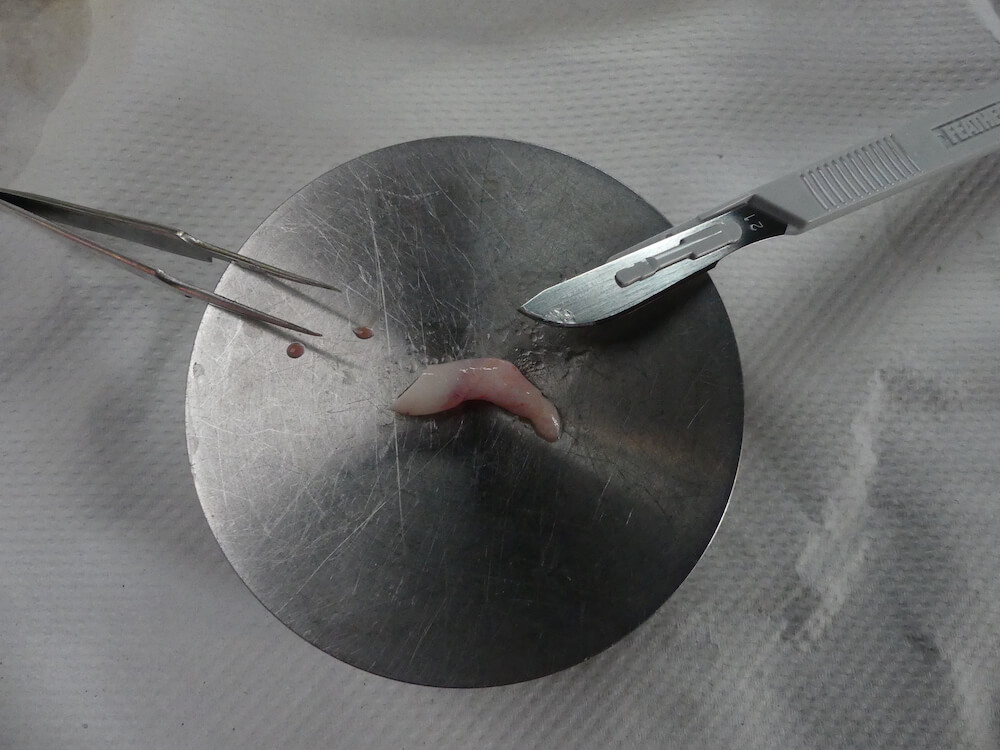

For a brief moment, time stands still. The influence of wind and waves alters the dart’s trajectory, but fortunately everything had been factored into the aim and the animal is hit and the sample, recovered. It is no more than 3 cm long by a few millimetres in diameter. The samples will be preserved until they get to the laboratory, where several analyses (contaminants and fatty acids) will be conducted.

The issue with a number of contaminants stems from their affinity with fatty acids, which allows them to accumulate in adipose tissue. For this project, I will focus on two groups of priority contaminants: flame retardants and organochlorine compounds. Emitted by cities and industries, these pollutants are found in the environment and gradually work their way up the food chain, eventually reaching whales. Some of these contaminants that have been banned for several years are still present in whale flesh and continue to affect the recovery of this population.

The next few days on the water are meant to be gorgeous, which will allow our team to continue our work in a leisurely manner. Many adventures will certainly be experienced before this project comes to an end, but I am aware of the privilege and the honour I have to study and to work with such exceptional animals.