Have you ever seen a blue whale? Although this giant of the oceans is found mostly in the high seas, there are a few special locations, including the St. Lawrence, where such encounters are occasionally possible. Regardless where one is on the planet, however, it is rare for tourists and scientists to observe a calf of this species with its mother. A new article published in Endangered Species Research suggests that this paucity of sightings may be attributable to the birth and weaning cycle of blue whale calves.

Mystery of Balaenoptera musculus

It’s a fact: observing blue whale mother-calf pairs is rare. Unlike other cetacean species such as the North Atlantic right whale, blue whales do not congregate in coastal waters to give birth, preferring instead deep offshore waters.

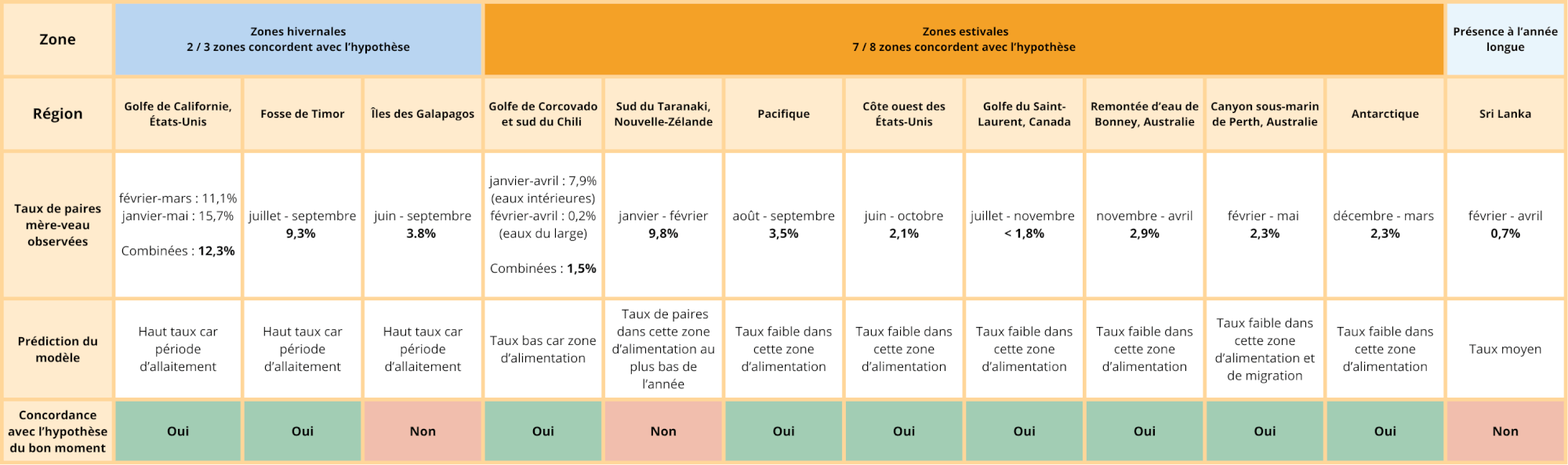

In the Gulf of St. Lawrence, in 45 years of observations, the Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS) has documented a mere 35 calves, i.e. less than 2% of all its sightings of this species in the region! On the west coast of the United States, of the 3,660 sightings made between 2005 2018, just 76 calves were seen, or 2.1% of these observations.

A study that combines others

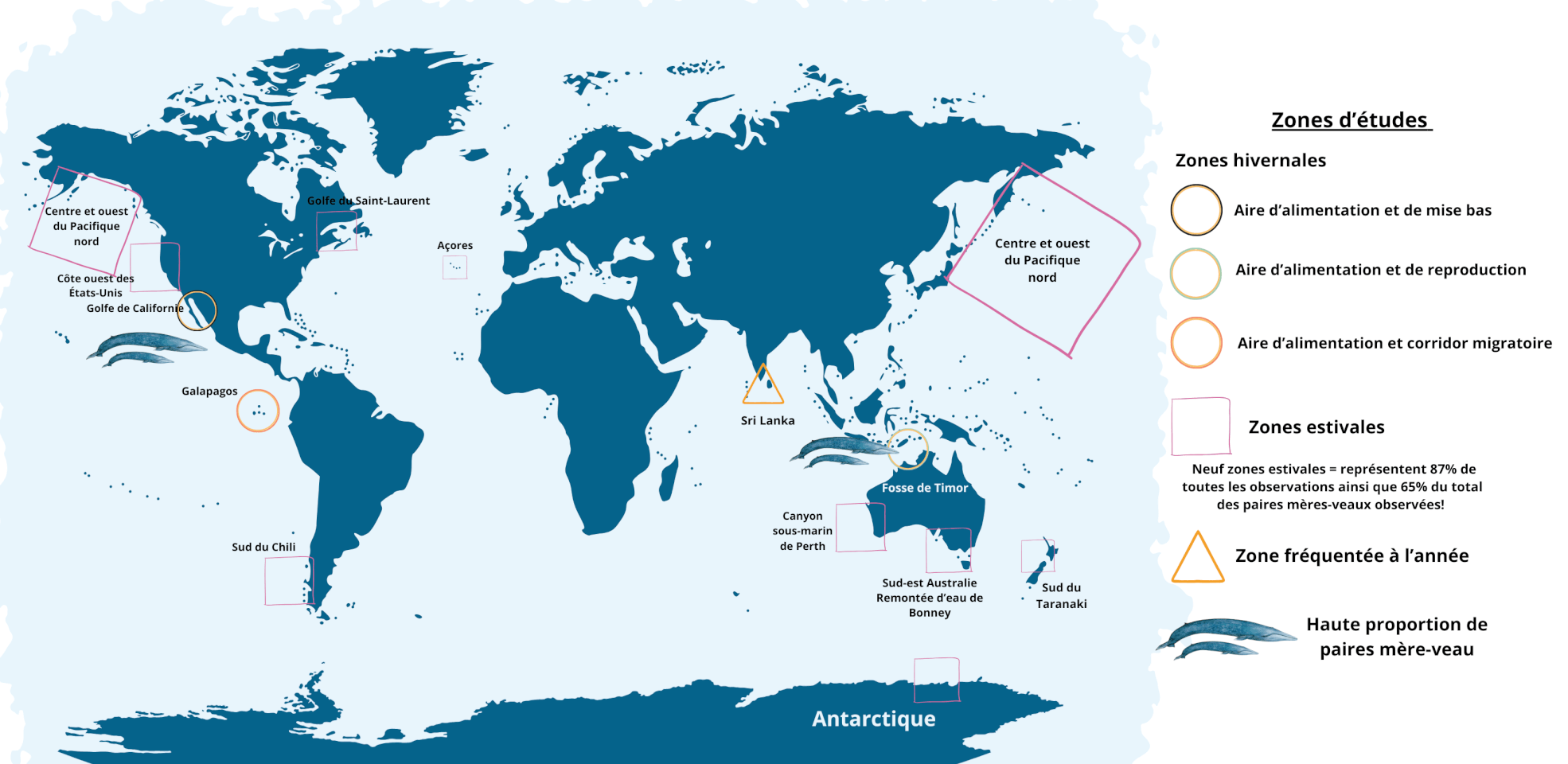

The author of the article, Trevor A. Branch, relied on historical whaling data collected by whalers over the years, as well as other long-term studies. A number of scientists involved in research on the species were also contacted directly.

To be considered, studies had to include a large number of observations involving more than 89 individuals and have been conducted over multiple seasons or in multiple geographic areas. The mother-calf pair ratios were obtained through 14 studies involving eight different blue whale populations inhabiting 12 different regions. Now that’s a far-reaching project! Five of the 14 studies concern wintering areas, while the other nine focus on summer feeding grounds. A total of 11,469 individual blue whales were sighted, including 339 (3.1% ) mother-calf pairs.

Numbers that don’t add up

Very few births or calves are observed, which is inconsistent with the rate of gestating females recorded in each blue whale population, which varies between 31 and 42%, depending on the region. Furthermore, female blue whales are believed to give birth every two to three years, i.e. much more frequently than observations of mother-calf pairs would suggest. The author of this meta-analysis proposes seven hypotheses to explain this disparity, including a low proportion of mature females in the population, a low calf survival rate (due to collisions, entanglements, poor nutrition, or killer whale predation), or the avoidance of aggregations by mothers and calves to defend themselves against killer whale predation, even though this is where field studies are generally concentrated. However, most hypotheses lack sufficient data to be confirmed and are therefore dismissed.

Dispersal

Blue whales do not always share common migratory paths, and some populations exhibit significant dispersal during their migration. In Chile, blue whales sometimes follow paths that are over 1,000 km apart. In the Azores, 10 tagged individuals each migrated in a different direction to their summer feeding grounds. In other regions, migration follows a single corridor. This regularly observed dispersal of both males and females explains why it is difficult to determine whether mother-calf pairs simply prefer to avoid aggregations, but a lack of data makes this impossible to confirm.

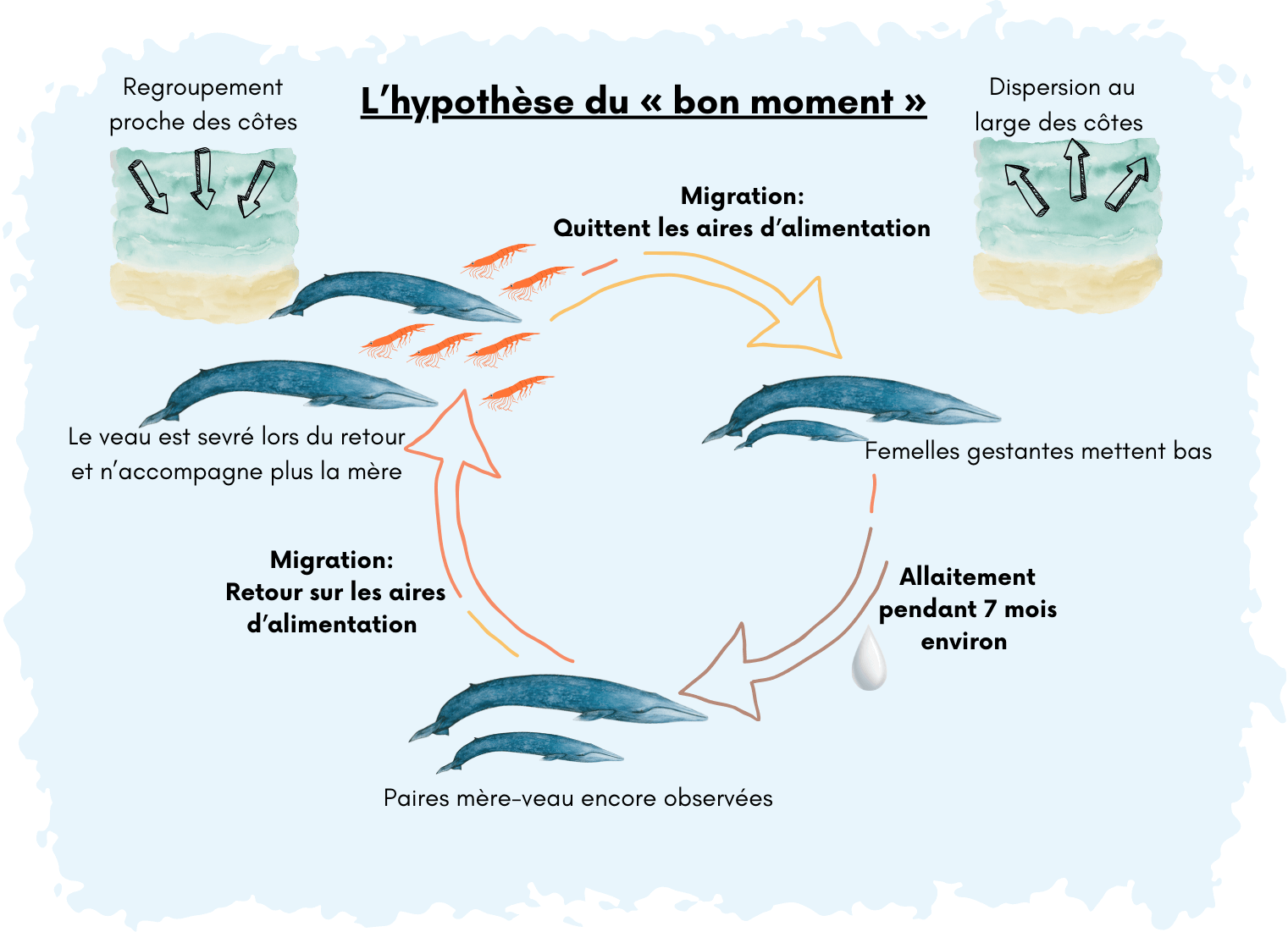

Timing hypothesis

According to the author, the most likely hypothesis is the timing of calving and weaning. After leaving their feeding grounds, pregnant females give birth and nurse their calves for approximately seven months. By the time they return to their feeding grounds the following year, the young are already weaned and no longer accompany their mother.

Blue whale nursing her calf.

Early weaning

To support this hypothesis, Trevor A. Branch uses a study conducted on female-calf pairs observed in Mexico’s Gulf of California in winter and spring. Eleven females were seen of that same year in California, only this time without their calves. The scientist concluded that weaning occurred either shortly after or in the course of their migration to their summer feeding grounds.

Overall, seven of the eight feeding areas are consistent with this hypothesis , with low rates of observed pairs being noted.

While this hypothesis is certainly plausible, few additional data exist to support it. Moreover, some data are inconsistent with what this model proposes.

The timing hypothesis offers a good explanation of the small number of observed mother-calf pairs, but it also has some limitations. Will this mysterious aspect of blue whale biology persist much longer?