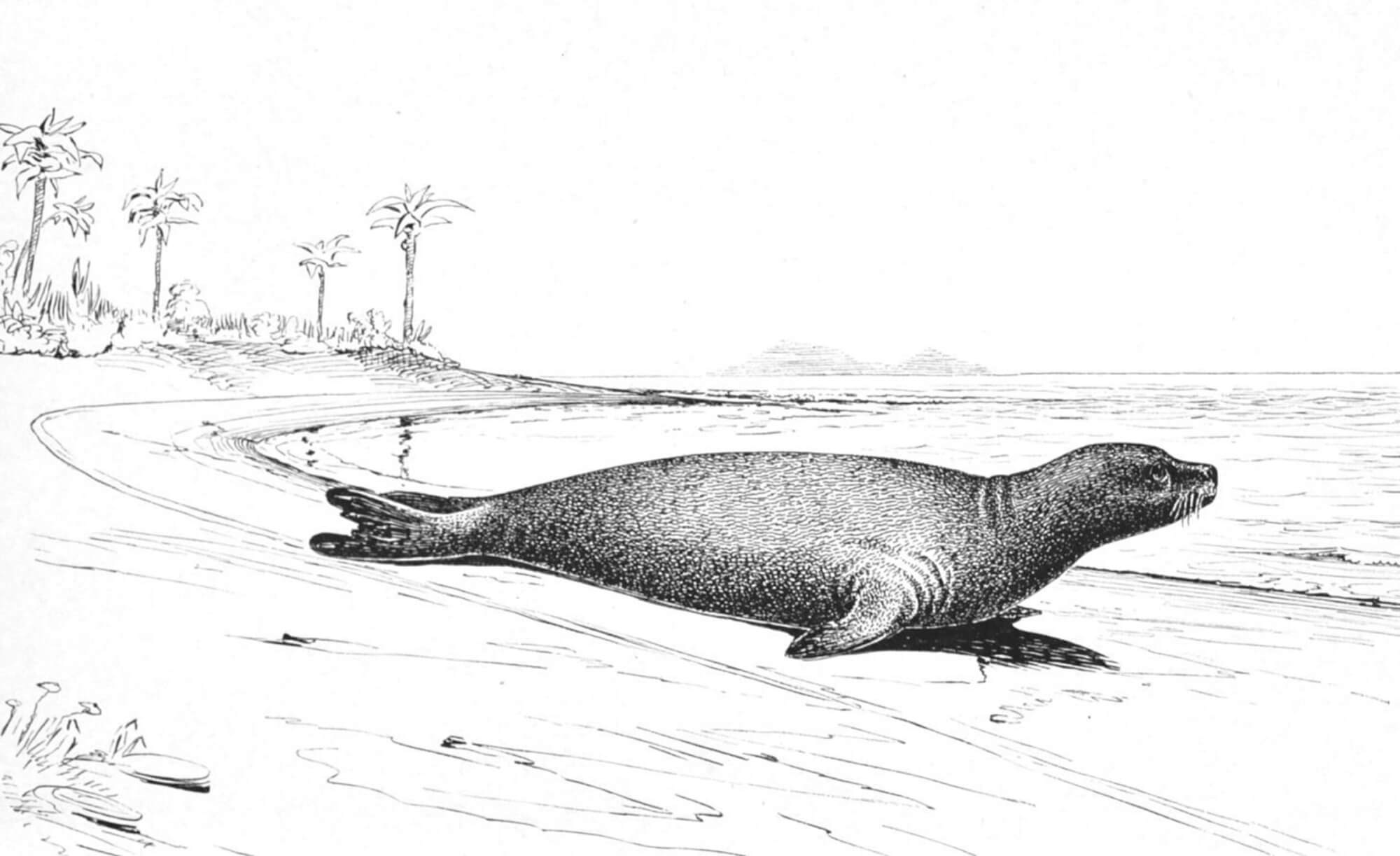

Named for their vague resemblance to black-robed monks, these animals have always been unique. Indeed, the three similar-looking species that make up this group are the only seals on the planet that live exclusively in tropical waters. They were once found in the warm waters of the Mediterranean, Hawaii, and the Caribbean. However, centuries of destructive human activity have taken their toll. Their decline was so steep that, until recently, it seemed unlikely they would survive into the 21 st century. Thanks to efforts to avoid such a sad fate, things have taken a completely different turn over the past decade. Let me tell you an environmental success story worth sharing: one that is at once sad, inspiring, and encouraging.

Vulnerable since the Middle Ages

Interactions between monk seals and humans are nothing new. Indeed, the Mediterranean species is mentioned in writings dating from the Antiquity. Various archaeological evidence also suggests the existence of connections, albeit less significant, in North America and in the Pacific between Indigenous peoples and the monk seals of the Caribbean and Hawaii, respectively.

Thus, in the centuries preceding our era, humans had already incorporated these animals into myths and legends, not to mention a number of toponyms. They also hunted them for their fur, blubber, meat, and medicinal uses. In the Mediterranean and Hawaii, this practice is believed to have been quite widespread. As a result, local populations had already declined considerably during the Middle Ages. However, the Caribbean species probably did not experience such a decline, as the population was already very small and challenging to hunt at the time due to other natural causes.

Due to their already precarious situation, the decline of the two American monk seal species accelerated with the colonization of the New World. Indeed, it is believed that the arrival of settlers in the Caribbean, and later in Hawaii, was followed by an uptick in hunting pressure followed by a decline in the number of monk seals, which were already rare at that time.

One more victim of the 20th century

The 20th century was not a kind one for several species of marine mammals, including monk seals. Already significantly vulnerable at the turn of the century, their populations continued to decline to the point that all three species were trending toward extinction.

The threats of previous centuries were compounded by others stemming from new human activities. For example, all three species were victims of the fishing industry, which led to a decrease in prey availability, attacks by fishermen, and incidental catches. Mediterranean and Hawaiian monk seals also suffered from habitat degradation and loss due to increased human presence, the growth of tourism, and the military presence on the Hawaiian Islands during World War II. Furthermore, in addition to both species falling victim to accidental collisions, the Hawaiian species suffered an increase in shark attacks, while Mediterranean monk seals were sought for public display in Türkiye.

By the end of the 20th century, the combined effect of all these impacts had resulted in a critical situation for monk seals. The Hawaiian species, which likely numbered around 15,000 individuals before the arrival of humans, now numbered just 1,400 individuals and was declining at a rate of 4.1% per year. Once abundant and present throughout the Mediterranean basin, the Mediterranean monk seal was now confined to a handful of individuals living in sea caves on a fraction of its historical range. And, in 1952, before anyone could even try to save the species, the last Caribbean monk seal died…

Race to save the last survivors

However, in the 1970s, things began to change for the better. Indeed, while it was too late for Caribbean monk seals, a faint glimmer of hope remained for the other two species. And it was by latching onto this hope that the countries whose native fauna included monk seals sought to reverse the sad fate of these animals.

Before they could begin, however, they had to await the arrival of an important element, i.e. the publication in 1965 of the first scientific data on the current status of the species. Realizing the urgency of the situation, Cyprus established the first legal protection for monk seals in 1971. Several countries followed suit, including the United States, Greece, and Türkiye, paving the way for numerous international treaties. In parallel, research on and awareness of these seals was growing, harmful fishing practices across the species’ range were the object of tighter regulations, and significant portions of monk seal habitat were being protected.

Despite all these efforts, the decline of the remaining monk seal populations continued at an alarming rate throughout the 21st century, with both species hitting record low numbers around 2012.

Efforts pay off

Indeed, new data indicate that the Hawaiian population is increasing at a rate of 2% per year and that the threshold of 1,500 individuals has recently been exceeded. In the Mediterranean, the species’ range is expanding, and the Madeira archipelago population is increasing by 3% annually.

This hard-earned success must therefore be celebrated. However, we must not lose sight of what made this recovery possible in the first place and what must continue to be done to allow monk seals to one day fully reclaim their place in tropical waters for good.

Learn more :

- (2001) Lavigne, D. M et Johnson, W. M. Hanging by a thread. Monachus Guardian.

- (2015) Littnan, C. Harting, A. et Baker, J. Neomonachus schauinslansdi, Hawaiian Monk Seal. (Royaume Uni) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: 1 - 17.

- (2025) Johnson, W. H., Karamanlidis, A. A., Dendrinos, P., de Larrinoa P. F., Gazo, M., González, L. M., Glüçlüsoy, H., Pires, R. et Schnellmann, M. Mediterranean Monk Seal (Monachus monachus). The Monachus Guardian.