As we enter into a sleepy winter on the St. Lawrence, a few belugas are quietly swimming here and there, harbour seals are resting on the rocks and two humpback whales were spotted letting out powerful blasts.

Belugas and seals

At the mouth of the Saguenay, a beluga slowly emerges from the blue waters, its snow-white body contrasting with the silvery reflections of the sun. In Rivière-du-Loup, another meeting point for those who love the sea, a trio of belugas was seen swimming offshore. Between Les Escoumins and Tadoussac, harbour seals bask on the rocks. Their lazy silhouettes curled up in the sun bring a touch of tranquillity to this maritime scene. One keen observer shares an observation of an animal from the weasel family: “I also observed an otter at the Tadoussac dunes, playing with seaweed at low tide!”

A number of definitions exist to determine whether a species can be considered a marine mammal, but broadly speaking, it can be said that any mammal that depends on the marine environment can be placed in this category. Polar bears, as well as certain populations of mink, fisher and otter that feed mainly on fish and marine crustaceans can therefore be considered marine mammals!

Humpbacks in Côte-Nord

Near Franquelin and Godbout, two blowing humpbacks are seen by one marine mammal enthusiast. Will these giants of the seas be migrating to warmer waters anytime soon?

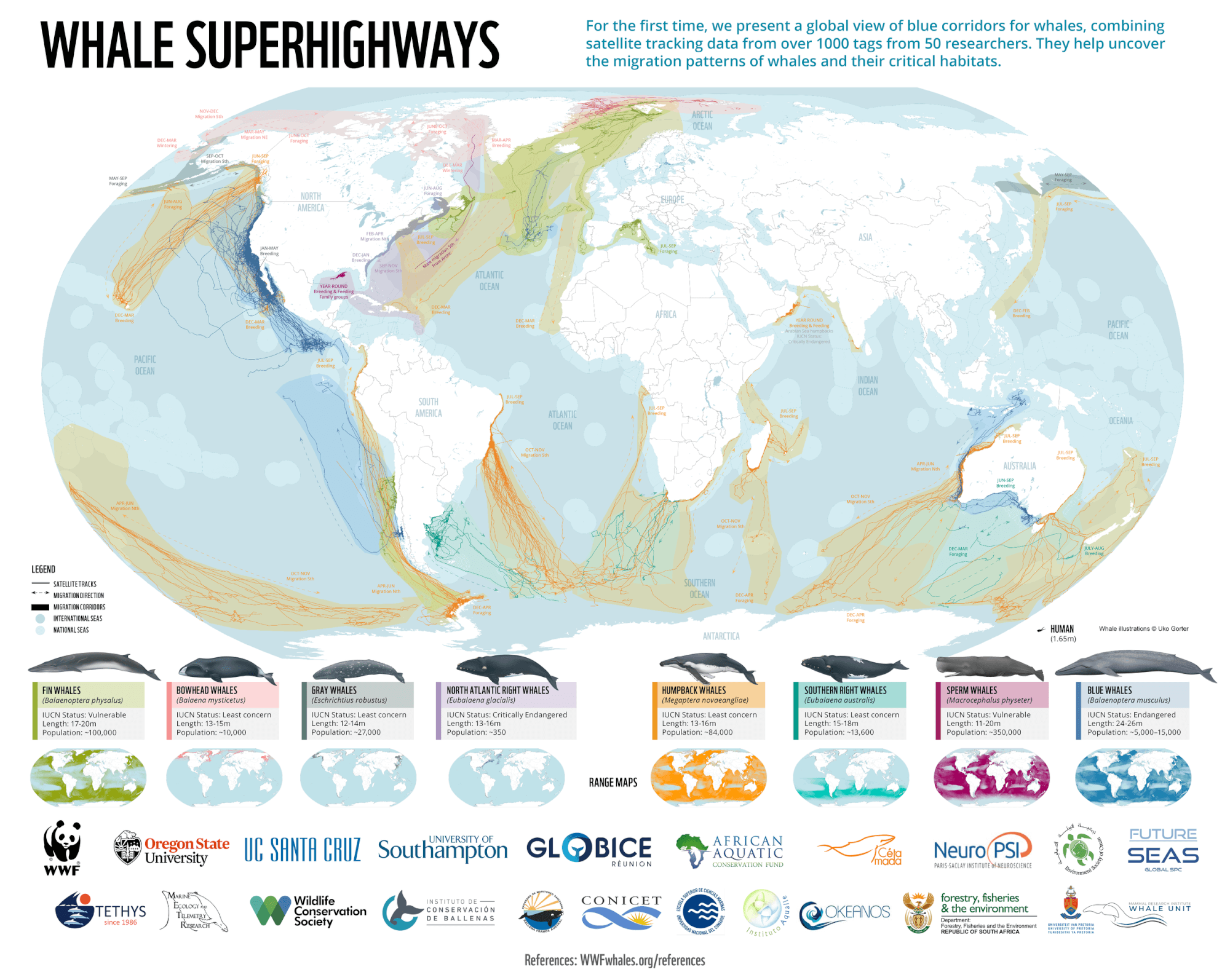

Unlike several species whose migrations remain mysterious, the movements of humpbacks are rather well known. In winter, they gather in the Caribbean to facilitate encounters between bulls and cows for the breeding season. This might also allow them to escape predation by killer whales during this important period. The migration route of humpback whales takes them on a journey that stretches more than 5,500 km. One male humpback even covered a record distance of over 13,000 km (article in French)! Once they arrive at their southern destination, they go the rest of the winter without feeding, living instead off their fat reserves. When summer arrives, humpback whales generally return to one of the species’ various feeding grounds, such as the Gulf of Maine, the coasts of Newfoundland or the St. Lawrence Estuary.

Any number of factors may signal to a whale that it is time to head south again, including the hormonal system (which is regulated by weather conditions), food availability or even ice formation.

In recent years, several individuals, especially young males, have lingered in the St. Lawrence into late fall, probably to take advantage of the region’s rich food supply. Will humpbacks continue to be observed in the estuary much longer this year? We’ll find out soon enough!

Thanks to all our collaborators!

Special thanks go out to all our observers who share their love for marine mammals with us! Your encounters with cetaceans and pinnipeds are always a pleasure to read and discover.

On the water or from shore, it is your eyes that give life to this column.

Odélie Brouillette

Marie-André Charlebois

Patrice Corbeil

Laetitia Desbordes

Diane Ostiguy

Renaud Pintiaux

Guillaume Savard

Andréanne Sylvain

Marielle Vanasse

And to all the others!

Additionally, we would like to acknowledge the following teams that also share their sightings:

Sept-Îles Research and Education Centre (CERSI)

Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals (GREMM)

Marine Mammal Observation Network (MMON)

Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network (QMMERN)

Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS)

Would you also like to share your observations?

Have you seen any marine mammals in the St. Lawrence? Whether it’s a spout offshore or just a couple of seals, drop us a line and send your photos to [email protected]!