By Marie-Maude Rondeau

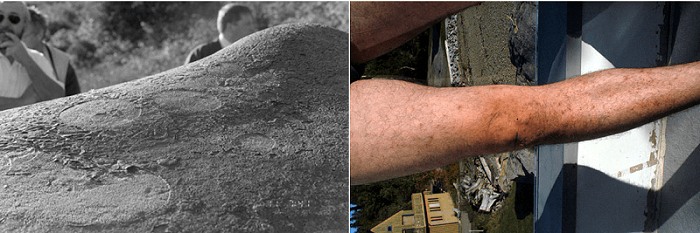

Ever heard of Valleau, the sperm whale whose carcass washed ashore in L’Anse-à-Valleau in 2003? Today, this individual’s skeleton is on display at the Marine Mammal Interpretation Centre in Tadoussac. Behind the reconstruction of this skeleton lies a colossal effort. Indeed, the GREMM team travelled all the way to Gaspé to flense the animal. And, in the process of this gruelling task, one team member even picked up a poxvirus! Yes, he contracted a zoonosis, i.e. a disease transmitted by an animal, as a result of physical contact between the infected area of the carcass and the skin. In fact, the person had a hole in his pants and his skin came into direct contact with the carcass. Within 48 hours of the incident, he develop a reaction throughout most of his body. Moreover, this was the first confirmed case of contamination of a sperm whale with this type of virus.

What is a zoonosis?

Zoonoses are diseases that can be transmitted from animals to humans. Little is known about zoonoses related to marine mammals and the risks are not yet well identified. These diseases can be transmitted by both living and dead animals and through direct or indirect contact. Pathogens can be bacterial, viral or fungal in origin.

Good to know…

Zoonoses are varied, not all well known and, as a result, not always properly treated. Furthermore, different pathogens can cause the same symptoms in their host, but the disease that causes these symptoms may require different treatments. Indeed, depending on the source of infection, one disease may be cured with antibiotics while for another, the latter will have no effect.

Moreover, for people not accustomed to working with marine mammals on a daily basis, one might tend to overlook the connection between the appearance of symptoms and a recent contact with an animal carcass. Effects may appear several days after initial contact. Some symptoms can even be flu-like at times… further adding to the confusion. Although many zoonoses manifest themselves as local infections (e.g. seal finger), other types of infections can have a more serious impact on long-term health.

Last summer, the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network (QMMERN) received a report of a grey seal carcass. The animal was in good condition, so the carcass was recovered for necropsy by Quebec’s wild animal health centre (CQSAS). At first glance, nothing about the animal appeared to be abnormal: no injuries or particular lesions were observed. The necropsy results, however, revealed a completely different reality. The grey seal died of a severe lung infection. Even in the absence of noticeable lesions, carcasses can carry bacteria or viruses and caution must be exercised, especially if one has cuts or wounds on one’s hands, which are the main entry points for pathogens. This is why our teams always wear gloves when handling a carcass.

Other indirect risks

When a whale is stranded, the blubber in the carcass quickly liquefies. And a whale has a lot of blubber! Approaching a carcass means carefully navigating slippery and sometimes bloody terrain. One must be careful, since the blood can be contaminated. Additionally, gas bubbles can sometimes form on the body and rupture without warning. One must also be cautious if a whale’s body is rocking from side to side in the waves at the edge of the beach. If one gets too close, they risk falling into the water and having several tonnes of whale on top of their head.

If you come across a marine mammal carcass, it is important not to touch the animal; instead, contact the Quebec Marine Mammal Emergency Response Network at 1-877-722-5346. The animal will be documented and possibly sampled or even necropsied, but never without proper precautions or personal protective equipment.