By Valeria Vergara, researcher with Ocean Wise’s Marine Mammal Conservation Research Program, specialist of acoustic communication in beluga whales and collaborator of GREMM.

[This article was first published on Ocean Wise’s blog. You can read the full original version here.]

In September 2001, during the aftermath of 9/11, much of the coastal ocean around North America was, for the first time in decades, quiet. In response to the terror attack, all non-essential boat traffic was halted along many shipping routes. What did this respite from acoustic pollution mean for the whales?

We have long known that underwater noise is a problem for cetaceans, profoundly acoustic creatures that rely on sound for many aspects of their lives. The sense of sound to many marine mammals is as important as the sense of vision to us, so noise is like an “acoustic smog” that makes many aspects of their lives – navigating, finding food, maintaining contact with one another – much more difficult.

The 9/11 temporary pause in acoustic pollution provided a perfect unplanned experiment for researchers led by New England Aquarium scientists. They creatively paired acoustic data from the Bay of Fundy, collected before and after 9/11, with data on the levels of the stress-related hormone glucocorticoid in the poop samples of North Atlantic right whales in the same area.

The study found that a sharp six decibel drop in noise levels was associated with a noticeable decrease in this stress hormone1. The whales were far less stressed than normal during these unusually quiet times.

Fast-forward to 2020. Life as we know it has slowed down to a near standstill as a result of the world-wide response to the Covid-19 pandemic. This is reflected in dramatically changed city soundscapes, with significantly less noise from buses, cars, and other transportation. If you break your isolation for a quick outing to the grocery store, you will probably notice that the streets are…well…quieter! And there is more: this marked shift in human activity has led to noticeably reduced vibrations of the upper earth crust, as measured by surface seismometers in several regions, including Belgium, Los Angeles, London, New Jersey, and France.2

So Covid-19 has unwittingly created a quieter surface world. What about underwater noise?

The bans of non-essential travel in many nations of the world, added to the shutdowns and labour shortages across maritime industries represent significant setbacks for commercial shipping, cruise ships and oil tanker sectors. For example, the world’s largest container shipping company (Maersk, a Danish company), cancelled more than 50 trips to and from Asia since February. Washington State’s Northwest Seaport Alliance, the fourth largest container gateway in North America, reported a 12% decline in total container volume for January and February 2020, compared to the same two months the previous year.

In Canada, all commercial marine vessels with the capacity of 12 or more passengers have ceased non-essential activities such as tourism and recreation. An unintended effect of these regulations may be reduced noise levels for our marine life, including various cetacean species at risk, such as St. Lawrence belugas, blue whales, North Atlantic right whales and southern resident killer whales.

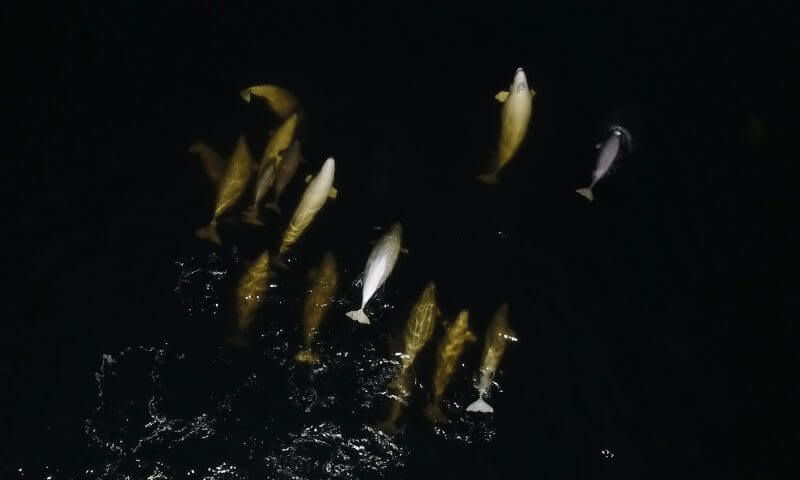

I cannot help but think about the belugas that I study year after year in the St. Lawrence estuary. Nicknamed “canaries of the sea” belugas are amongst the most vocal mammals of the planet, and underwater noise severely impacts their ability to communicate effectively and remain in touch with one another, especially for mothers and their newborn calves, as our most recent study has shown3.

Our Quebec-based research partners at GREMM (Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals) reported that belugas are already being seen near Tadoussac (our summer field-work hub). It may be too soon to evaluate the impact of the new pandemic-related regulations on the St. Lawrence soundscape, but once tourist season starts, we may just see the quietest period the whales have had in years!

Some restrictions introduced by Transport Canada intend to protect vulnerable Northern Canadian communities from the spread of the virus. For example, the measures prevent cruise ships from mooring, navigating or transiting in Canadian Arctic waters4. These measures will remain in place until October 31, 2020, the end of the shipping season in most of the Arctic. Given the ‘boom’ in cruise ship tourism in the region5 in recent years, as the warmer and less icy Arctic has become more navigable, this year may be a reminder of less noisy times for Arctic marine mammals like narwhals, belugas, and bowhead whales.

Locally [Valeria writes from Vancouver], BC Ferries has reduced their service across multiple routes, effectively cutting sailings in half. Given that BC Ferries is the single biggest producer of noise in British Columbia waters, this will have significant effects on whale habitat. Whale watching companies have also suspended operations, and the start of the cruise ship season has been delayed until July 1st at the earliest. For endangered southern resident killer whales these changes probably offer a welcome respite, as noise and disturbance are one of the three main threats to their recovery, along with reduced availability of chinook and contaminants.

I reflect on these bittersweet unintended consequences of the pandemic for marine life. There is little doubt that we are experiencing an unprecedented hiatus in ocean noise. It is too early to tell how long this will last, and what the impacts will be on marine mammals, but I hope that these trying and unprecedented times teach us something about the direct, and often immediate, impact of our actions on our oceans.

Sources

- 1. (2012) Rolland, R. M., Parks, S., Hunt, K. E., Castellote, M., Corkeron, P. J. , Nowacek, D. P., Wasser, S. K., and Kraus, S. D. Evidence that ship noise increases stress in right whales. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279 (1737): 2363-8. 10.1098/rspb.2011.2429.

- 2. (2020) Gibney, E. Coronavirus lockdown have changed the way Earth moves. Nature 580, 176-177

- 3. (2019) Vergara, V., Wood, J., Ames, A., Mikus, MA., Lesage, V., Michaud, R. Mom, can you hear me? Impacts of underwater noise on mother-calf contact calls in endangered belugas (Delphinapterus leucas). Abstracts of the International Workshop on Beluga Whale Research and Conservation. March 12-14, Mystic, CT, USA.