In the presence of watercraft, blue whales reduce both the duration and depth of their dives. A recent simulation-based study conducted by Fisheries and Oceans Canada shows that boat disturbance prevents blue whales visiting the St. Lawrence from reaching the best schools of krill, a worrying finding for this endangered population.

In 2019, the same team of scientists showed that only a small proportion of krill swarms are dense enough to be worthwhile for a hungry blue whale. Indeed, if the swarm is too sparse, the whale risks expending more energy on its feeding manoeuvres than it will get from gulping down these tiny crustaceans. How does the presence of boats influence the scientists’ previous conclusions?

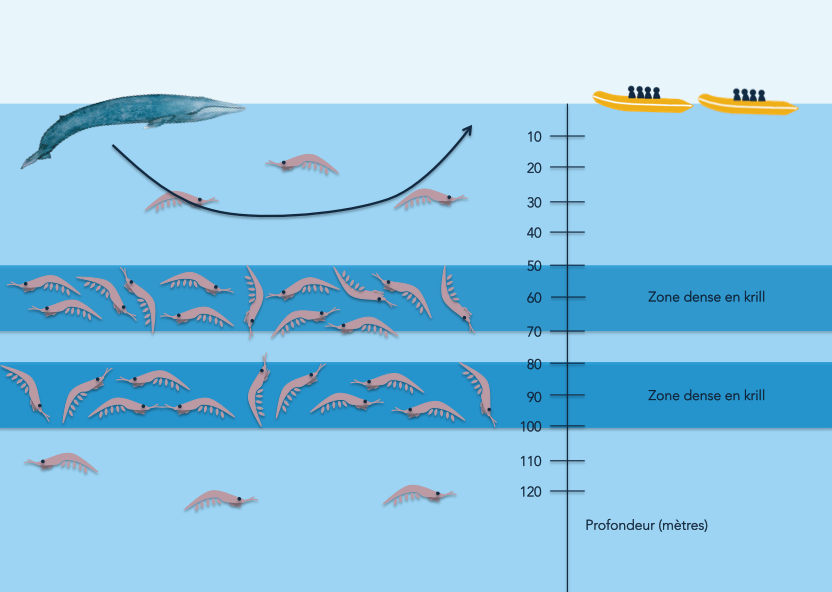

While the average dive time for a blue whale is 10 minutes, it drops to 4 minutes whenever a boat is less than 400 metres away. As a result, the whales don’t have the time to dive as deep, either: 70% of 4-minute dives take place in the first 30 metres below the surface, even if food is to be found at greater depths.

As a result, according to the simulation developed by the research team, a whale disturbed 3 hours a day in the Estuary would get 22% less energy than an animal that was able to feed at depths of 50 to 70 metres. In the Estuary, it is in this layer that we find a greater density of northern krill, one of two species of krill found in the St. Lawrence. And if boats are within 400 metres for 10 hours, the animals’ energy intake would be slashed by 74%, once again according to the simulation carried out by the researchers. “The simulation provides a good idea of the energy loss that boat disturbance and lower krill abundance can trigger, though the exact figures should be interpreted with caution,” explains Marie Guilpin, lead author of study.

Depending on the feeding ground and the krill species considered by the model, the impact of disturbance on foraging can vary. In comparison, the energy loss associated with three hours of boat presence would be equivalent to a 5% decrease in krill density in blue whale habitat. Such a figure may appear negligible. However, changes in diet are magnified when scientists combine the impact of disturbance with the decreases in krill density that are to be expected with climate change. “The importance of krill for blue whales, as their sole food source, is the reason behind the krill fishing moratorium in Canada since 1998,” points out Marie Guilpin. These discoveries clearly underscore the importance of abiding by the regulations for navigating in the presence of whales. In the St. Lawrence Estuary and the Saguenay Fjord, all watercraft much maintain a distance of 400 metres from any threatened or endangered species, i.e. blue whales, bottlenose whales, North Atlantic right whales and belugas. Elsewhere, such as in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, this distance is 100 metres.

Potential effects on reproduction

For blue whales, summer means foraging, since once they return to their winter range they do not eat for the remainder of the year. This is why potential declines in the abundance of krill (their only prey) as well as in their feeding ability due to boat traffic are of particular concern.

If blue whales are not getting enough to eat, this could explain why researchers have not observed them in large numbers in recent decades. Indeed, because it is so energy intensive, reproduction can be postponed in animals that are undernourished.

In order to verify whether the blue whales that visit the St. Lawrence can theoretically store enough energy to reproduce, the research team plans to develop a new model that will take into account energy expenditure not only during the foraging season, but also during migration and reproduction.