It was 1999, and my life was about to change. I had just completed my studies in biology and was selected to work for GREMM as a research assistant. Whether it was aboard cruise ships or GREMM’s research vessel, my main role was to photo-ID and tally individuals of the various species of large whales that visit the St. Lawrence Estuary year after year. During my stints from 1999 to 2001, 2014, 2016, and now each of the past five summers, I have witnessed how the equipment we use in the field has evolved over time. I will therefore attempt to share these changes with you, as well as the long-standing interest I have in this work.

The challenges of film photography

When we first started 25 years ago, we were still using negatives and focusing our camera lenses manually. So we really had to hone our reflexes to capture moving whales! In three photos, we had to capture the animal’s chevron, its back, and its peduncle as clearly as possible to identify each animal and be able to confirm that it was the same individual recurring from year to year. This process is called photo matching.

Once back in the office, we had to develop the negatives, print the photos on paper with the correct black and white contrast—yes, the photos were black and white—and then identify, sort, and match them, which was extremely time-consuming. All this required tremendous rigour and attention to detail. Today’s digital cameras focus automatically. Sorting and matching photos is done on a computer.

New technologies

The evolution of computers has been nothing sort of revolutionary and has led to many changes in how data are processed and used. In the beginning, we had heaps of printed photographs stored in huge filing cabinets and two Excel files that contained all our data. Nowadays, photos are digital and can be pulled up from our hard drives with a few clicks of the mouse, and information is distributed across over a dozen interlinked databases. This database architecture was developed internally to optimize the processing of the photos and data collected every year. The interface allows photos to be directly viewed in the desired context as well as any associated information. These data are all compiled in a centralized catalogue and combined to describe the story of each individual. Thanks to these new tools, the efficiency of processing field data and managing the central photo catalogue has been greatly enhanced.

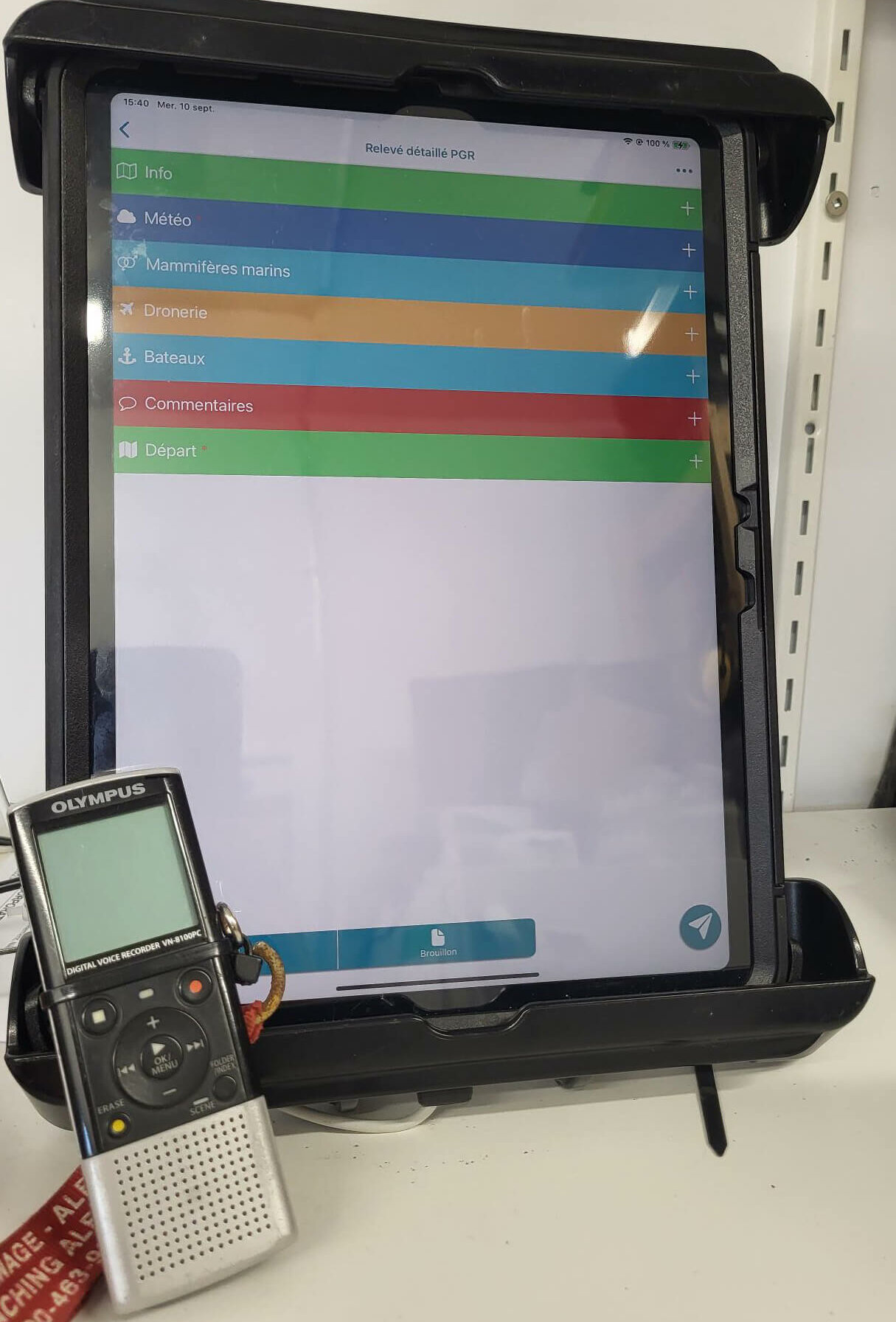

In the field, in addition to taking photographs, we record parameters such as cloud cover, wind, wave height, visibility, the number of boats, the number of whales, information related to the photographs, and much more. In my early years, we used cassette recorders to record these data, which were later followed by digital recorders.

When we returned from the field, we had to listen to these files to enter all the information into an Excel spreadsheet, which made for a lot of office work! This year, we once again took advantage of advances in digital technology by using online forms through the Kizeo app. Now we can enter data directly in the field on an iPad, after which they are automatically transferred to an Excel spreadsheet in the desired format. No more long office hours listening to ourselves talk into a voice recorder!

Our daily tasks include cropping all the photos so that they show only the animal. A new tool based on artificial intelligence (AI), is currently under development that aims to automate this task. The AI would be able to recognize the animal in the photo, and we would only have to check for errors. Initial tests conducted this past summer are very encouraging. Another time saver!

Over the past four years, a major innovation has found its way into my work: the use of drones on the research vessel. This tool, which allows us to peer down on whales from above, allows us to gather a treasure trove of information, but is not without its share of challenges. Takeoffs and landings are carried out by the photographer to minimize the time the device is flying in proximity to the boat. During these manoeuvres, the pilots must compensate for the effects of the wind, waves, and current, all of which have a considerable influence on the movement of our small craft. With drones, we can fly over the animals and capture aerial images that show the colour patterns of both flanks simultaneously.

We use these images for photo-identification, detecting potential interactions with humans, and photogrammetry. Perhaps one day, drones alone will be enough to monitor the large whale species that frequent our area?

In the age of social media, the team created a Facebook group for people who work on the water to help us locate and identify animals. My role in this group involves answering ID-related questions and creating species-specific (blue, fin and humpback) photo albums. Mariners can use these albums as a reference to identify cetaceans at sea. One of the positive aspects of the creation of this group is that it has helped strengthen ties, the spirit of sharing, and collaboration with other people on the water!

What hasn’t changed about my passion in 25 years

What I love about my work is running into familiar animals and seeing that they’re doing OK. It’s always exciting to be on the water, breathing the fresh air of the St. Lawrence, and admiring the vast sea- and landscapes!

When I’m aboard cruise ships, whales can sometimes be scarce. In these situations, it’s always fun to be able to show passengers other animals that we sometimes forget about, such as seals, birds, or porpoises. Passengers are always amazed to witness this beauty.

Lastly, what I really enjoy about my job is the teamwork on the research boat that we leverage to successfully capture quality images. Good communication skills are necessary to coordinate the work, for example, handling the drone, positioning the boat against the wind and current to take good horizontal photos, etc. Additionally, a positive team spirit is also important to successfully record all these data as efficiently as possible. On cruise ships, it’s being around people who are passionate about the sea and whales and being able to share incredible moments with them that for me will always remain unforgettable. After all these years, the joy of forging friendships with these folks will never change!